#60: "The mail room is filling!"

The Titanic's mail room, 1.6 million letters, and five brave men

My brain is currently filled with nothing but bunny fur and early-twentieth century history. As if researching the Titanic for two weeks straight wasn’t enough to launch me a hundred years into the past, I’ve also been reading Last Train to Paradise, Les Standiford’s book on Henry Flagler’s rather frantic and laugh-in-the-face-of-nature quest to build a railroad to Key West.

Much of the early twentieth century in the U.S. and perhaps Western Europe can be defined that way: people hellbent on pushing ahead, nature and safety be damned, all for progress, progress, progress. The Florida East Coast Railway hurricane disaster(s), the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, the Dust Bowl…

And maybe most notorious of them all, the Titanic.

RMS Titanic - the mail room of dreams

Even before the 1997 movie, the tragedy of the Titanic captivated our collective imaginations. And since James Cameron brought Jack and Rose to the big screen, most of us probably think of the ship on Cameron’s terms: the bougie upper crust, the opulent staircase, the (lack of) lifeboats. When the ship was built, it was touted as unsinkable, the height of luxury, and its future ferrying folks across oceans seemed a certainty for years to come.

That being said, honestly? Despite watching Titanic in theaters three times (and devouring the terrible made-for-TV 1996 miniseries we rented from Movie Gallery waiting for Titanic’s VHS release), I don’t think I fully comprehended just how luxurious the ship was til I started researching.

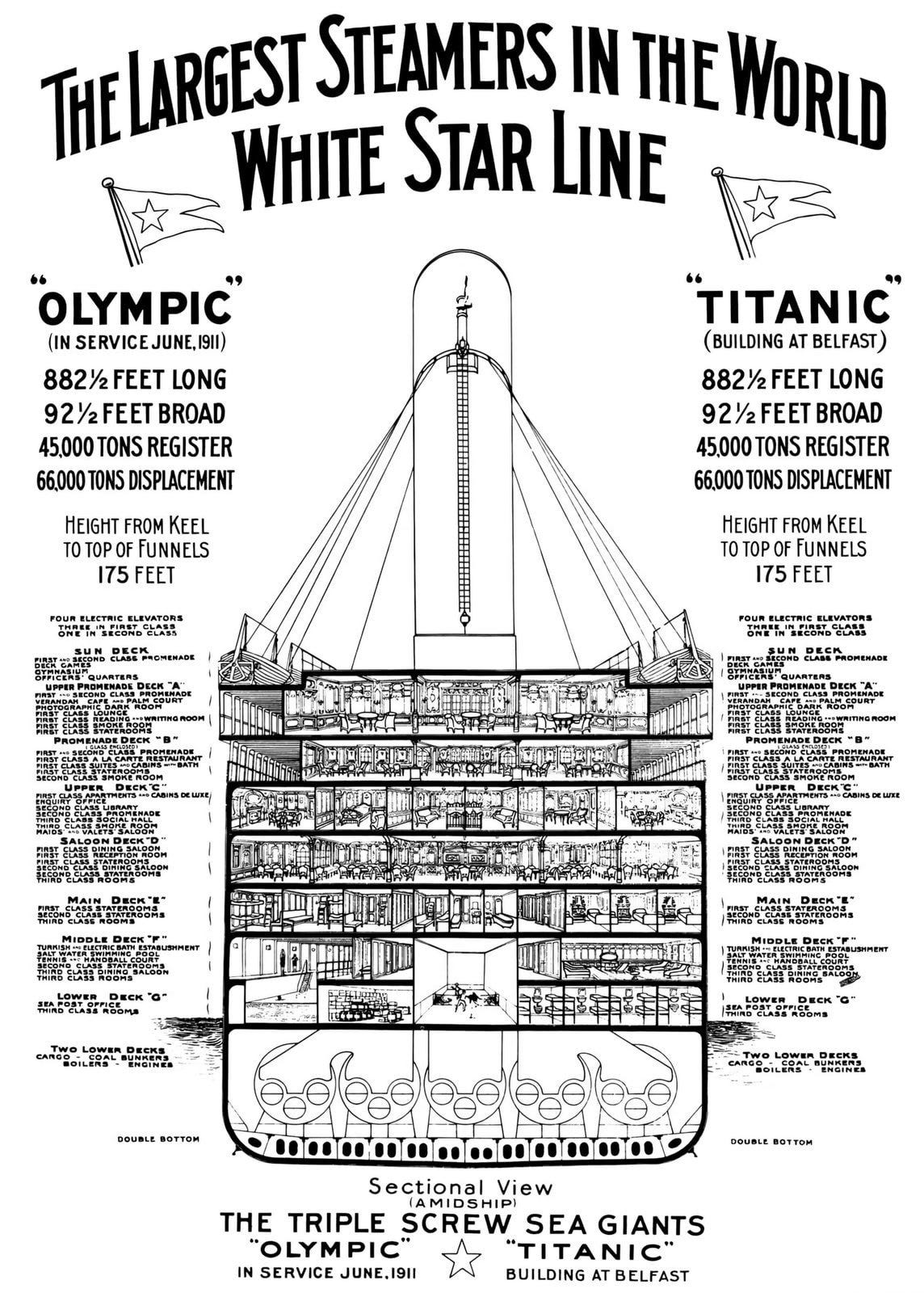

In this 1912 ad for the RMS Titanic and its sister ship Olympic, outlandish perks include multiple dining spots, a French style café a la carte, libraries (plural), a “Turkish Electric Bath Establishment,” a salt water swimming pool… the list goes on:

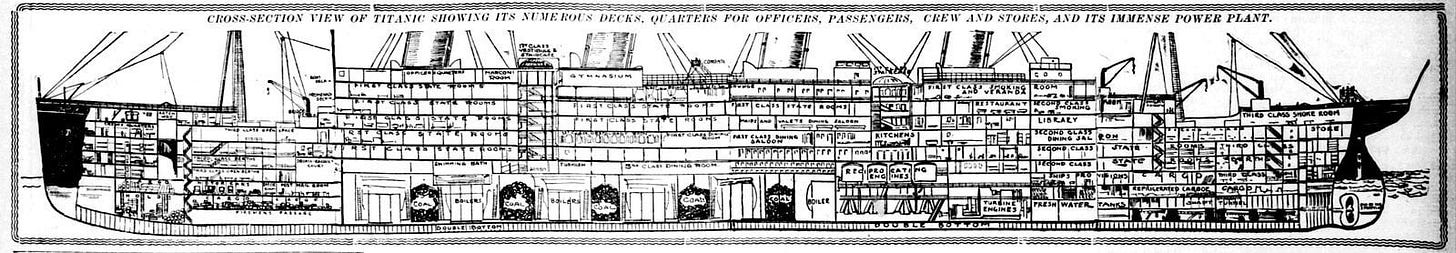

The ad only skimmed the surface. There were other goodies too, like a squash racket court. And below that court, on G deck near the bottom of the ship, sat the mail room.

The Titanic’s mail room may have been small relative to the ship itself, but it wasn’t an afterthought; it was the body and soul of the steamer. Because even though the Titanic was a luxury liner that carried both the wealthy and regular folks like me (and probably you) across the Atlantic to emigrate, visit family, or take on a new job, it was first and foremost a mail service.

With a name so iconic it needs no title, it’s easy to forget the Titanic was technically the RMS Titanic - The Royal Mail Ship. Co-commissioned by the British Monarchy and the US Government, the Titanic’s job was to ensure mail got delivered1.

On top of the 1300 passengers who boarded the Titanic, 908 crew members lived and worked alongside them - five of whom belonged to the post.

On April 10th, 1912, the ship set off from Southampton, a port town in the south of England. And while there’s a rather romantic idea that folks boarded the ship once before sailing off into the sunset, the Titanic actually made two more pitstops before setting off in earnest: Cherbourg, France, to pick up 274 more passengers (including American Benjamin Guggenheim) and then to Cobh2, Ireland for another 123 passengers.

And on April 11th, 1912, when the Titanic left Cobh for its ill-fated journey towards New York City, it carried not only 2240 passengers and crew, but 1700 bags of mail - some six million letters and packages - with it.

👨🏻✈️ The mail carriers

Being an international ship ferrying mail from England and Ireland over to the U.S., it only made sense that the five mail clerks hailed from both the US Postal Service (USPS) and the Royal Mail.

John Richard Jago Smith

A 35-year old originally from outside Cornwall, John Richard Jago Smith seemed like a quiet man with a quiet, happy life. After spending his teen years working his family farm, Jago Smith became a postal worker around 1898, at 21. I think a change like that is something most of us can relate to. Who didn’t leave home at 21? At that age, I packed up my entire life and moved to Moscow on essentially a whim, eager to carve something out that had nothing to do with my hometown.

It seems Jago Smith had the same idea, moving 160 miles (~260 km) away to build a life separate from his family farm3. He started as a sorting and telegraph clerk before joining the Southampton postal office’s sea post track. In Southampton, Jago Smith fell in love. And when he boarded the Titanic, he left behind a fiancée waiting for him to return4.

James Bertram Williamson

Born in Dublin, James Bertram Williamson lived a life peppered with tragedy. Growing up, many of his siblings were stillborn or didn’t make it past infancy, and in his early twenties his brother and father died within a year of one another. After those losses, Williamson supported mother through his job with the Royal Mail.

Around 1910, Williamson struck out to Southampton, maybe for a fresh start; perhaps the job was more lucrative. While working for the Southampton post, Williamson seemed to have started building a community for himself, and was even known to be seeing a woman named Gladys who lived up the street. But like the other sea post clerks, Williamson boarded the Titanic and left that hopeful future behind5.

William Gwinn

William Gwinn loved his wife Florence. Well experienced working international post, after years sorting for the Foreign Mail Section, Gwinn shifted gears and became a sea post clerk, a well-paid job for the time.

By then familiar with the sea post life, in April 1912, Gwinn was in England and assigned a routine return voyage to work the SS Philadelphia from Southampton to his home in Brooklyn.

But then he received word from family that his wife Florence was dangerously ill. Stressed, Gwinn swapped his posting on the SS Philadelphia for the Titanic. This newspaper article lists the SS Philadelphia as leaving in May. Gwinn likely figured coming home a month sooner to see his wife was worth changing plans.

Obviously, Gwinn never arrived home. And in a bitter twist, his wife’s illness hadn’t been as serious as the family made it out to be; she survived, the family withholding news of his death for months6.

John Starr March

With 48 years under his belt, John Starr March was no stranger to shitty luck on the sea. Despite finding himself in what the Smithsonian called “eight separate emergencies” in only eight years of work as a sea post clerk, March loved what he did, reportedly finding solace in it after his wife passed in 1911.

Even though his line of work stressed the ever-loving hell out of his two adult daughters (rightfully so - can you imagine your parent nearly drowning eight times for work? No thanks! I like my mama right where she is in the Houston ‘burbs, thank you very much), March had no plans to quit. According to an obituary in The Newark Star, March used to “laughingly reassure the fears of his daughters by saying that he would never meet death by drowning.“

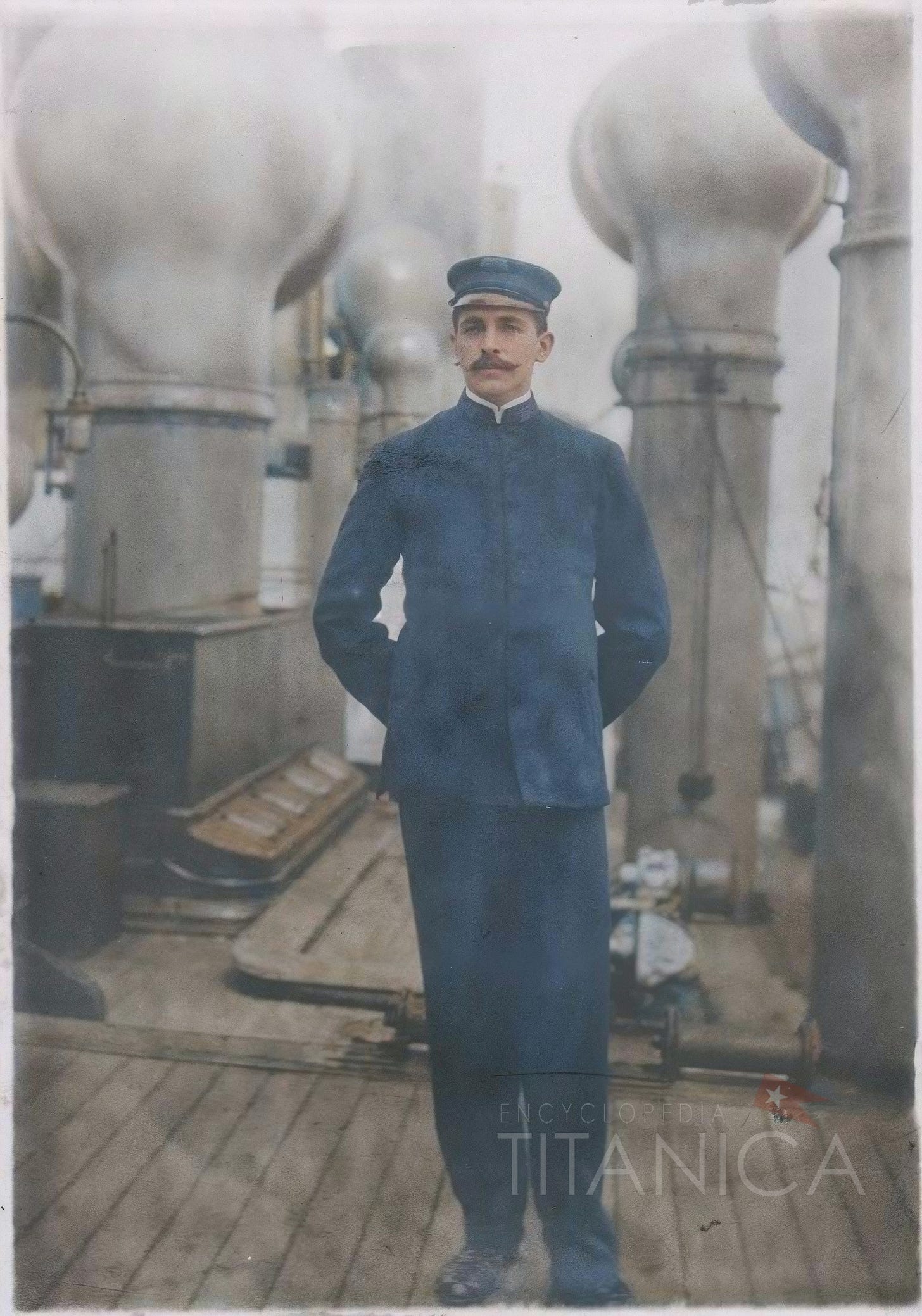

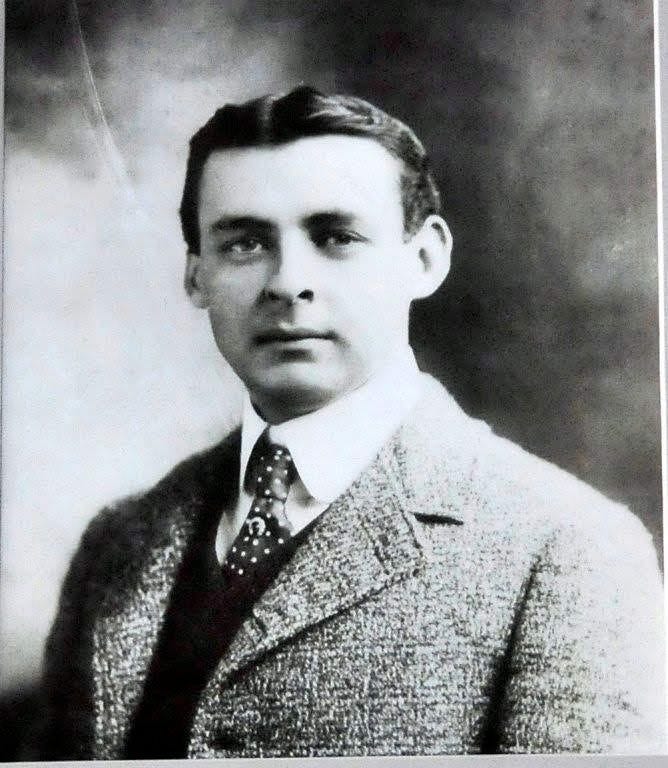

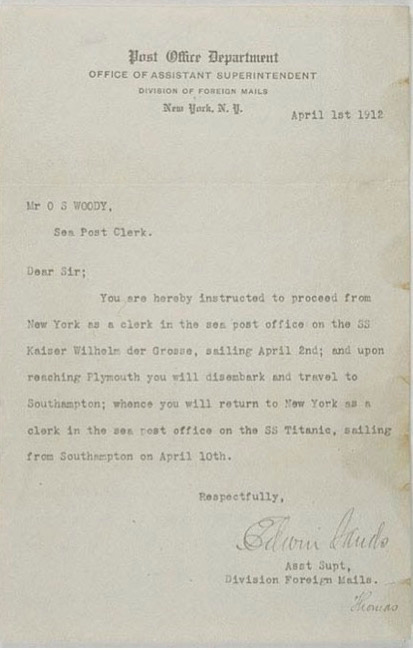

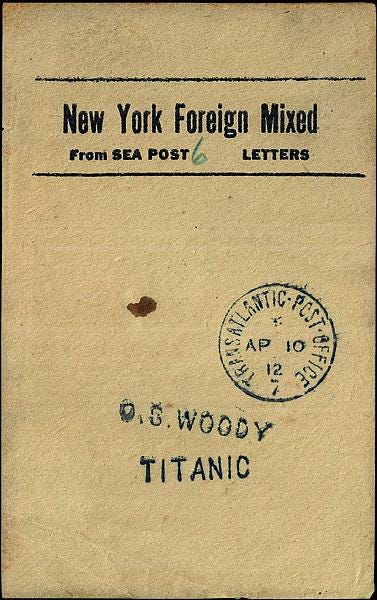

Oscar Scott Woody

Of them all, one postal clerk’s luck might’ve been the worst. The night of the iceberg was Oscar Scott Woody’s 41st birthday. Coming from Roxboro, NC and a freemason7, Woody had worked in the USPS for years, spending over a decade on the Railway Mail Service, before trying his hand at the Sea Post Service8.

In a very unlucky letter sent on April Fools’ Day, Woody received word he would be working the Titanic’s mail room:

And so, crossing the ocean on his birthday, things took a turn for the worst.

🌊 The mail room is filling!

On the night of April 15th, 1912, our five men were celebrating Woody’s 41st birthday9, enjoying a group dinner in their private quarters. At some point, at least one of the men - our pal William Gwinn - left to go to bed. While we’ll never know why, he was the only one among them whose circumstances weren’t merry ones; worried about his wife, I’m sure it wasn’t easy to go ham for his temporary colleague’s birthday.

All the same, the night had likely been a good one so far: five relative strangers on an adventure, paid a comfortable salary and fed well to work in a ship so elegant, even the mail room was posh. And only a few days’ out from New York City, half the men would soon return home, while Jago Smith and Williamson would get to spend a few days in an iconic city.

But at 11:40 PM, the Titanic hit an iceberg, and their simple birthday dinner was ripped apart. Scraping the iceberg along the length of the hull tore wounds in the side of the ship, striking six compartments - including one adjoining the mail room. Only minutes after impact, their room began to flood.

In this 1956 interview, Titanic survivor and former steward James Witter recalled his experience encountering our men:

When he’d first heard the first thud of the collision, Witter thought perhaps a propeller lost a blade. Taking it on himself to investigate and hopefully soothe passengers, he asked around in the stewards’ quarters. When nothing seemed amiss, he lingered to chat with coworkers in the hallway. Then, Witter said,

“I was standing there talking to two or three fellows and the carpenter came along and I heard him say, "The bloody mailroom's full of water."

I said, "What's that? Mailroom full of water?"

He said, "Yes."

I said, "Well, what about those bulkhead doors forward?"

He said, "They're not holding, Jim.”

Through fate or accident - as he helped lower a lifeboat into the frigid waters, he literally tumbled in while trying to save a flailing passenger - Witter survived, helping us piece together the mail room’s final moments.

But although some employees - the carpenter, mechanics, now Witter - knew things were grave, the postal clerks hadn’t yes realized how extensive the flooding was. Like everyone else on board, they’d bought into the myth of the Titanic as “unsinkable.” Thinking the leak would be contained, the men prioritized their duty to protect the mail. All five got to work - Woody on his birthday, and Gwinn arriving from his quarters still wearing his nightclothes. The room flooded fast, but the men fought to save what they could, lugging some two hundred bags up from G deck to C deck10. Eye witnesses saw Gwinn (again, clad only in nightclothes in icy sea water), lugging sacks of mail, one under each arm, from the rapidly rising flood. And as the men lugged the bags, one of our five clerks flagged down Officer Joseph Boxhall, who recalls him shouting, “The mailroom is filling!”

Prioritizing the mail may seem insane now, but the lower decks had watertight doors. In theory, the crew could have sealed this part of the ship off successfully, preventing the Titanic from sinking, and so the men assumed the mail was worth saving.

Once they realized it was a lost cause, Woody, faithful to his job to the last, shoved mail slips into his pockets as they abandoned the sacks, likely hoping to sort it out upon rescue and account for at least some of what had sunk.

Instead, the slips were recovered on his body when he was found in the ocean days later. For his dedication, he’s the only postal worker in the U.S. with a post office named in his honor. March’s body was also later recovered. Gwinn, Williamson, and Smith were never found.

🚢 What to do with the mail now

Not a single letter from the ship’s mail room survived. And still, at the bottom of the ocean, there are 1.7 million pieces of registered mail - some 6 million pieces of mail in total - undelivered.

It makes you wonder about all the small ways these letters could have changed lives. Which lovers never reconnected? Estranged siblings? Packets of money sent to struggling parents? Gambling debts never collected?

While there is debate about whether or not to remove things from the wreckage, many assert - Smithsonian included - that the Titanic and all its contents be left intact. The ship, its wine bottles and bowler hats and water glasses and stray shoes, are evidence of lives lived and 1500 individuals’ horrific deaths.

The mail, however, is another story. Remember in November, when I talked about the dramatically named Congress of the Universal Postal Union? Post offices have a legal obligation to deliver the mail internationally - and because the Titanic’s post spans two different countries, the idea has been floated about bringing the mail up to send it to its rightful owners.

Although that seems bozo, paper and wood products often keep well in water under silt - like this part of a wood structure made half a million years ago that is calling our understanding of proto-humans into question11, this 300-year-old book salvaged from the Archangel Raphael shipwreck in the Baltic Sea, and these 80-year-old letters recovered from a WWII-era shipwreck. It’s very likely the sacks of mail still have letters inside that could be restored and, theoretically, sent.

While the costs of salvaging this mail - plus the arduous process of preserving and restoring it - make the idea unreasonable, it’s still an interesting thought. Is there an ethical obligation to deliver mail, even if it’s a hundred years late - like this 103-year-old Welsh postcard?

And since the wreckage was only discovered in 1985, most would-be recipients were likely dead by the time the post office even knew where to find this mail. Who do you send letters to, over a hundred years late? The original address, or whatever latest descendants the post can track down?

Some post offices do their best to deliver dead letters to descendants, but with 1.6 million letters lost to the bottom of the ocean, it seems the love letters, estranged family talks, burning secrets, crime confessions, rambling and vulnerable 4-page missives about chronic depression, business transactions, life-changing inheritances - all those sparks and flares that make up human lives when we interact with loved ones across the ocean - are lost for good.

See you next week!

I know I’m several days late; thank you for your patience. We had to take our sweet baby bunny boy to the emergency vet and keep him there several nights! It was very stressful. He’s happy as a clam now, energetic enough to hop on the dining table like a hooligan, and spoiled rotten with his faves (fennel, cilantro, and flowers).

All my love and salt-encrusted, long lost mail forever,

Nikita, Your Snail Mail Sweetheart

Remember the requirements of the Congress of the Universal Postal Union?

The city now known as Cobh was known as Queenstown at the time, but changed its name during the Irish War of Independence in 1920.

US and Canadian friends: if you’re reading this going “160 miles/200 km? That’s chump change for moving! That’s a commute!” - remember that the state of Alabama is about as large as all of England. The guy went pretty dang far!

John Richard Jago Smith's biography in Encyclopedia Titanica

John Bertram Williamson's biography in Encyclopedia Titanica, again

"Fire & Ice: Hindenburg and Titanic" from the Smithsonian National Postal Museum

Conspiracy??

Titanic’s Mail Clerks, part of the Smithsonian National Postal Museum exhibition Posted Aboard RMS Titanic, 2001

“Titanic: Life, death aboard the ship that sank 100 years ago today,” LA Times, April 2012 and HJ518 - State of Virginia General Assembly House Bill commemorating the bravery of Oscar Scott Woody, March 2012

Since the article came out two years ago, I often reread it and still get dizzy contemplating that span of time and humanity and all the wooden structures our ancestors half a million years back made that we’ll never know about, The total cultural significance of that! Our histories!!! Ahh!!!!! Time!!!!!!