#54: "Parcel post rules now prefer bees to babies"

The strange US history of sending kids via mail

Like nearly every U.S.-raised writer with a deadline this past week, I’ve been staring at the cursor and chewing on the words rattling like loose teeth in my head, trying to figure out what the hell to say.

In a time where it feels like democracy is a dog that’s fixing to crawl under the trailer to die1, I somehow agreed to write about something as goofy as the 1910s trend of sending children through the U.S. mail? Seriously?

The past week I laid on the couch and binged TV, mended clothes, baked a cake, had a good cry. But after a few days, I realized that making art and writing to y’all about history are the only things in my arsenal, the only way I know how to interact with an increasingly uncertain world - and engaging with other folks’ art and writing is the only way I perhaps know how to move forward. Maybe that’s true for you, too.

So here’s a story about a quirkier part of U.S. history, an early example of viral hearsay that captured U.S. imaginations. A TikTok challenge done in bloomers, if you will.

Because a dose of something funny may be as good a balm as we’re gonna get.

📦 The parcel post

Throughout US history, communication between the states has been an issue. While that breakdown is largely metaphorical now, back in the late 1800s, those communication issues were literal. Letter delivery was erratic as is, particularly to rural areas, and the United States Postal Service (USPS) had no method for delivering packages of any kind.

In 1878, the dramatically named Congress of the Universal Postal Union (someone please write an action-packed graphic novel about them; I’ve already got too much on my plate!) drafted an accord between countries spanning five continents, promising one another to deliver international mail sent to the countries’ respective addresses2. That meant if someone in Japan mailed something to Kentucky, the U.S. had an obligation to get that mail delivered.

The U.S. was still only a few years past the mayhem of the Pony Express, and this accord spurred a gradual revamping of the USPS. While I’m sure that wasn’t an easy ask for any of the countries belonging to the Congress of the Universal Postal Union, it posed a unique challenge to the U.S. because y’all, it’s big.

Logically, sure, we all know this, but for context, once I took a train from Oregon to New York and it took three days (I even made a video about it). Sometimes I don’t think my European friends really grasp the country’s breadth, so for anyone thinking “ok sure whatever,” here’s a great video scaling the US to the UK:

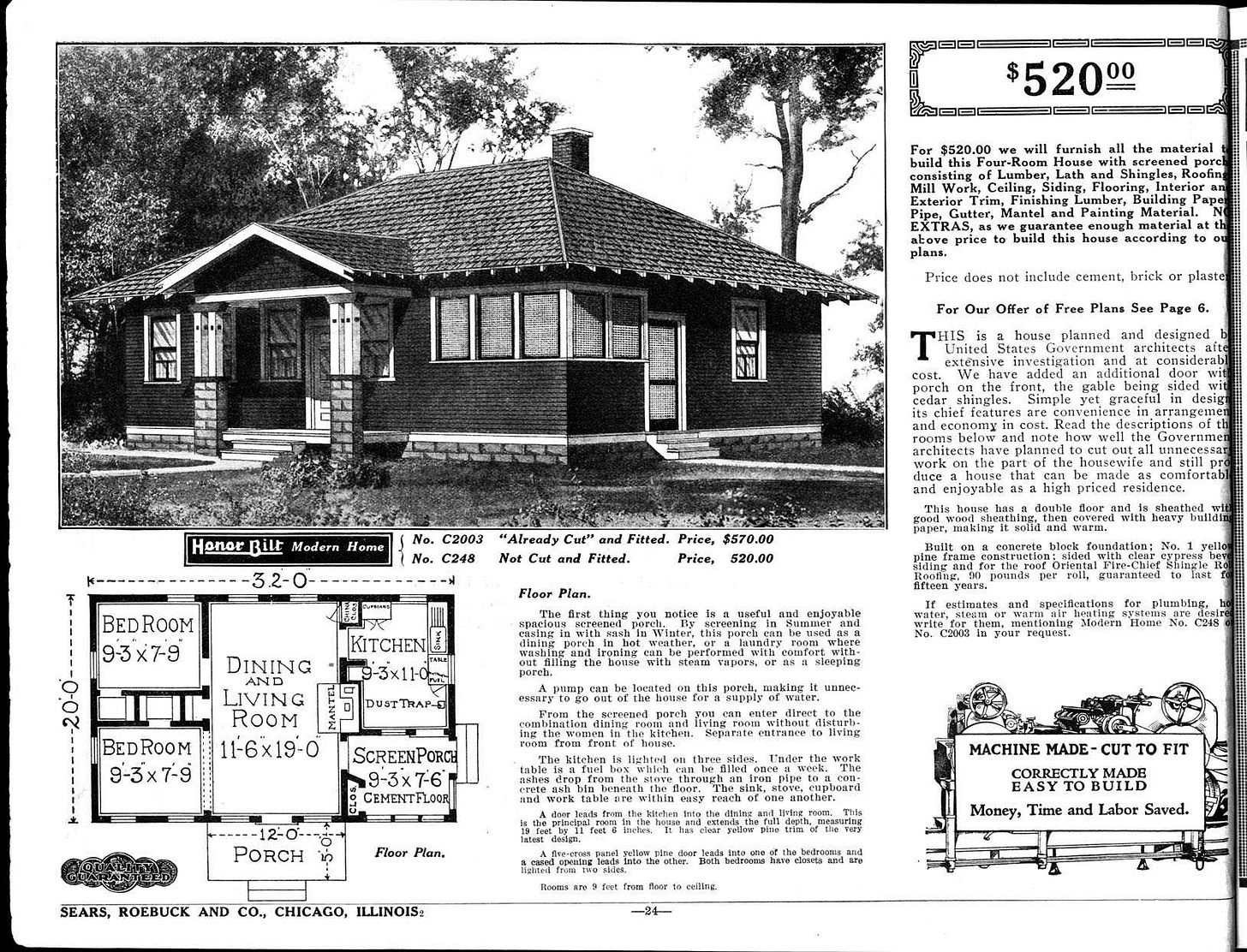

With that in mind, it’s no wonder that, despite the 1878 agreement, the US didn’t cement a consistent parcel post delivery system for another 35 years. Without a USPS system in place, private companies oversaw parcel delivery as it grew more common in the late 1800s, including shipping new-fangled mail-order catalogues and the honestly fascinating Sears Roebuck (RIP) mail-order houses.

At the time, the USPS didn’t even deliver letters to rural homes; they’d collect mail for folks at the nearest post office. Packages were out of the question - a major issue when you consider that over half the US population back then lived in rural areas (versus under 20% today). Private delivery companies charged exorbitant fees, wringing rural folks dry in their quest to get mail-order goods.

For rural US Americans, fetching your mail from the post office wasn’t a matter of an inconvenient hour on horseback; it sometimes took days to reach their nearest post office. Even after the USPS finally implemented home letter delivery for all residents - rural and otherwise - in the late 1890s, they dragged their feet on parcel delivery. Why rush, when companies were making such a profit gouging prices?

Citizens got progressively pissed, putting more and more pressure on the government to make the USPS deliver parcels at a reasonable rate. And after almost twenty years of drama, when one of those delivery companies announced a large stockholder dividend (meaning profits3 fattened investor pockets while screwing over half the country), Congress finally listened to the people’s mounting rage.

On January 1, 1913, the parcel post service opened up shop, accepting packages within these strict size limits4:

“The size of a parcel… must be not more than three feet and six inches in length. It must not weigh more than eleven pounds. The sum of its length and girth must not exceed six feet.”

The parcel post’s success was astounding. By the 6th of January - a measly five days after opening - nearly 1600 post offices around the country handled four million packages total5. That’s almost a million packages per day!

Of course, in the good ole US of A, if folks can test the limits of a rule, they will. A small handful of enterprising people ready to save a buck realized there was one thing they could mail, something that was cheaper to ship than it was to buy train tickets for: their own damn children.

👶 Bye, Tommy! Don’t bite the postman!

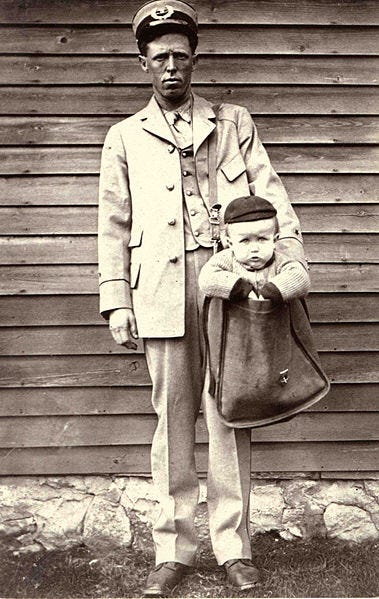

The first recorded human package to be sent?

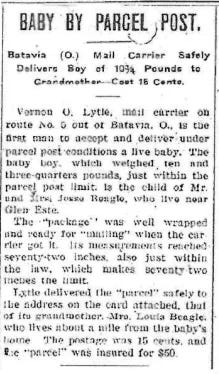

A little chicken nugget named James Beagle, Jr. In Ohio, James and Mathilda Beagle wanted their 8-month-old baby to spend some time with his grandmother. And with their kiddo clocking in just under the then-weight limit of eleven pounds, they decided to say “fuck it6” and send him up the street through the mail.

Vernon O. Lytle, mail carrier… is the first man to accept and deliver under parcel post conditions a live baby. The baby boy, which weighed ten and three-quarters pounds, just within the parcel post limit, is the child of Mr. And Mrs. James Beagle, who live near Glen Este. The ‘package’ was well wrapped and ready for ‘mailing’ when the carrier got it. Its measurements reached seventy-two inches, also just within the law, which makes seventy-two inches the limit.

Lytle delivered the ‘parcel’ safely to the address on the card attached, that of its grandmother, Mrs. Louia Beagle, who lives about a mile from the baby’s home. The postage was 15 cents, and the ‘parcel’ was insured for $50.

In the Beagles’ defense, back then $50 was about $1592, or €1486, so they did make sure baby James was taken care of.

And just like that, a trend was sparked. As the weight and size limits for parcels expanded, so did the age range of kids parents sent.

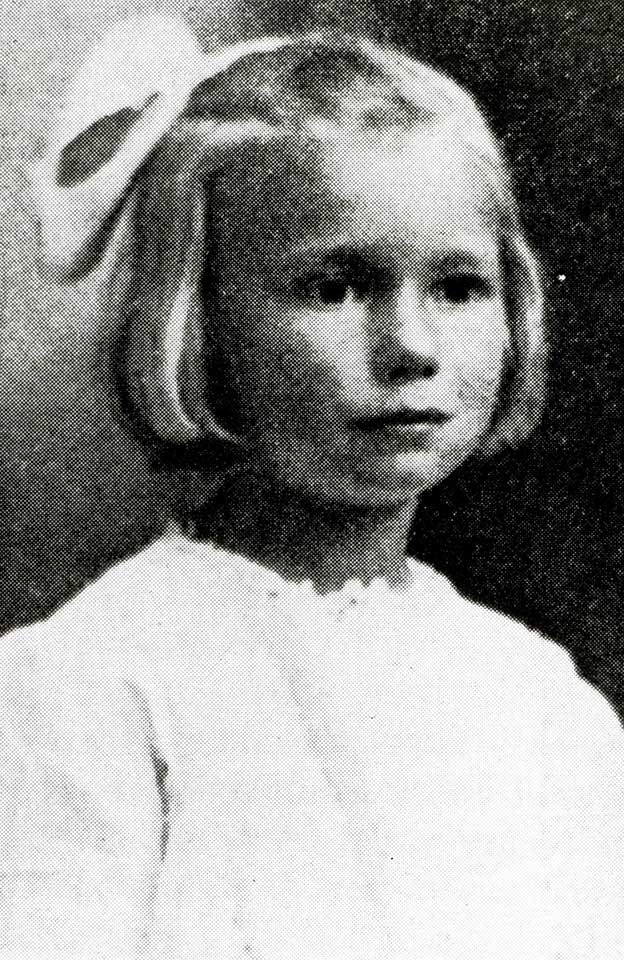

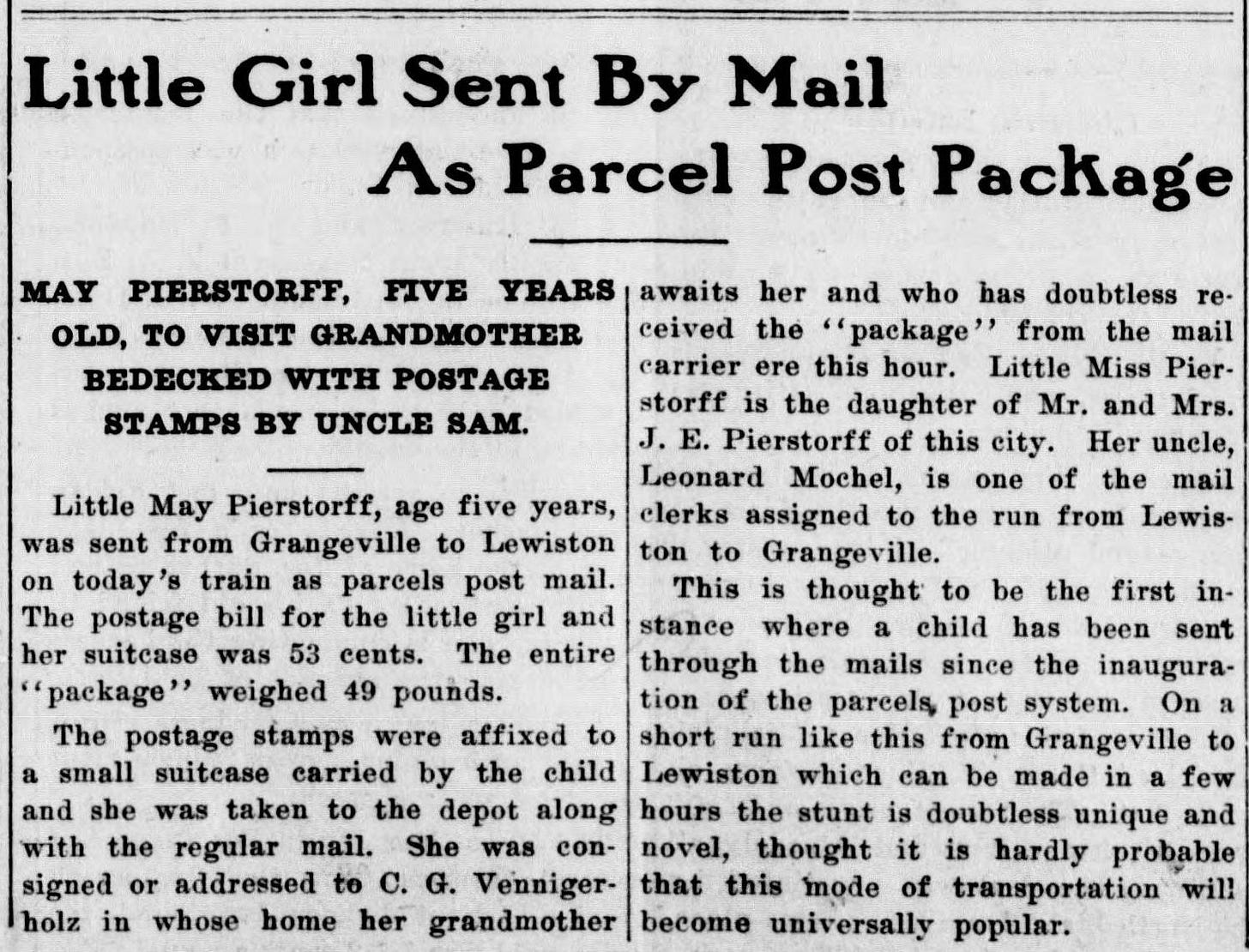

It’s not as if people were mailing their children daily, but it happened often enough to make headlines those first few years7. Other kids came and went through the post, but none were more famous than little May Pierstorff:

This article, published February 1914 by the Idaho County Free Press, mistakenly says she’s the first kid to be sent this way:

Little May Pierstorff, age five years, was sent from Grangeville to Lewiston on today’s train as parcels post mail. The postage bill for the little girl and her suitcase was 53 cents. The entire “package” weighed 49 pounds. The postage stamps were affixed to a small suitcase carried by the child and she was taken to the depot along with the regular mail. She was consigned or addressed to… her grandmother… who has doubtless received the “package” from the mail carrier ere this hour.

[May’s] uncle, Leonard Mochel, is one of the mail clerks assigned to the run from Lewiston to Grangeville.

This is thought to be the first instance where a child has been sent through the mails since the inauguration of the parcels post system. On a short run like this from Grangeville to Lewiston which can be made in a few hours the stunt is doubtless unique and novel, though it is hardly probable that this mode of transportation will become universally popular.

Not all kids got as much media attention - probably because their family members weren’t postal worker employees who could pump up the story and make it seem even sweeter.

One of my favorites that I can’t seem to find anything substantive about is Edna Neff, a four-year-old girl whose mother shipped her from Pensacola, Florida to her father’s in Christainburg, Virginia (that’s about 725 miles, or 1100 kilometers) in 1915. A divided family at the time wasn’t as common as it is today, and as the furthest distance recorded for any shipped kid, it makes you wonder what exactly happened that made Edna Neff’s mother ship her so far on her own. There’s a juicy story in there, one that I don’t think we’ll ever get the full of.

The only reputable information about Edna’s journey are the train order details: she weighed just under the then fifty-pound limit, had a placard with 15 cents worth of stamps and her destination information pinned to her shirt, and made the journey solo8. That’s under five bucks to travel hundreds of miles! Amtrak could never.

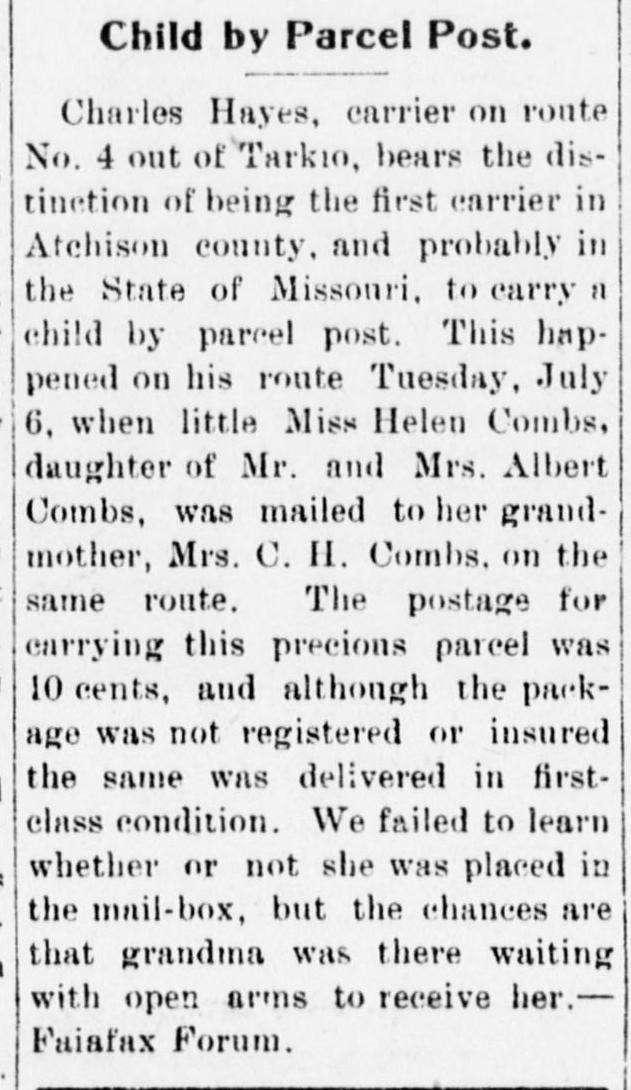

And later that year, another kid was sent up the road - three-year-old Helen Combs:

Charles Hayes… bears the distinction of being the first carrier in Atchison County, and probably the State of Missouri, to carry a child by parcel post. This happened on his route Tuesday, July 6, when little Miss Helen Combs, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Albert Combs, was mailed to her grandmother on the same route. The postage for carrying this precious parcel was 10 cents, and although the package was not registered or insured…[it] was delivered in first-class condition. We failed to learn whether or not she was placed in the mail-box, but the chances are that grandma was there waiting with open arms to receive her.

I think one of my favorite things about these old articles is what a kick the journalists got out of these weird stories. Across the country, basically everyone thought the idea of mailing kids on the cheap was hilarious.

Everyone, that is, except the Postmaster Generals themselves.

📬 Cut it out

Almost right out the gate, the Postmaster Generals tried to put a stop to folks sending their kids through the post. In 1914, after little May made headlines on the train, the Second Assistant Postmaster came out and said, “Alright, folks, pack it in.”

Queen bees are the only living things that can be handled by parcel post, according to a decision by Second Assistant Postmaster General Stewart, who was asked if a baby could be transported through the mail.

G.W. Merrill, postmaster of Stratford, OK, notified the department that J.B. Denton wanted to send a two-year-old baby from Twin Falls, Idaho to his post office, and [said] that there were no regulations in the parcel post system covering the case.

Reference to the regulations showed Postmaster Merrill to be correct, and the department ruled that all human beings and live animals, except queen bees, are barred from the parcel post.

In theory, case closed. But one thing you can never do is tell a parent what to do with their own kids, I guess, because people kept slapping stamps on their children and trying their luck.

Over a year later, a mother sent her three-year-old Maude9 through the parcel post:

For the first time probably in the history of the parcel post a baby has been sent through the mails.

Tuesday the… three-year-old child of Mrs. Celina Smith, little Maude Smith, was sent from her home in Morgan County… as a parcel post package.

The baby’s mother has been visiting here and was taken ill. She wanted to see her child, and… the family… dressed [Maude] up in her best bib and tucker, pasted the necessary stamps on a streamer sewed to her little pink frock and took her to the post office. There she was given in care of the United postal authorities, who promptly started her to Jackson, where she arrived safely today. From the post office here she was placed in a wagon used by the parcel post and conveyed, eating candy, which however was not included in the government regulations, to the home of Mr. James Haddix, where her mother received her with open arms.

The distance from Caney to Jackson is about thirty miles and the youngster seemed to enjoy her trip thoroughly.

While thirty miles seems like an easy enough jaunt nowadays, a horse-drawn wagon or carriage can travel about thirty miles per day, leaving the kid in the care of postal workers for hours. In retaliation, the postmaster and the higher-ups investigated this case, reprimanding the local post offices to pressure them to stop accepting children.

When news spread of potential consequences for the postmen, shipping children became even less popular, but it wasn’t until 1920 that a postmaster ruled one final time that no more children can come through mail, as they didn’t fit the classification “of harmless live animals which do not require food or water while in transit.”

And that was the final nail in the coffin of this strange little decade of shipping your kids one place to the next.

Trusting your neighbors

While we can look back and wonder what the hell these parents were thinking, back then, your postal worker was a regular fixture in your life, someone you saw every day and who you’d share news with. You trusted them. These parents - except for the mysterious Edna Neff’s - almost never handed their kids off to absolute strangers. They were trusting their community members to keep their children safe. And in a world chock full of helicopter parenting, batshit anti-neighbor conspiracy theories, and general animosity, the earnest faith in your postal worker can feel hard to wrap your head around.

But maybe it’s nice to remember that people have the capacity to be good, offer support, and keep each other safe.

See you next week!

Go get yourself something tasty, take a bubble bath, call an old friend, or go to a matinee and watch something that makes you laugh really really hard. Personally, I’ll be baking, hosting an embroidery workshop, and trying not to refresh my news apps too many times in one day.

Take care of yourselves - and don’t go shipping your babies in the ding dang mail!

All my love and stamps smudged by sticky-fingered children forever,

Nikita, Your Snail Mail Sweetheart

If you think I’m being hyperbolic, I present Exhibit A, Exhibit B Exhibit C, ‘dictator for a day,’ a repeat of the Mexican ‘Repatriation’ Act of the 1930s… the list goes on and on!

I found the original document! Universal Postal Union: Convention of Paris, June 1878

Capitalism!!!

“Maximum Parcels Under the New Parcel Post Law” by W.H. Bussey for The American Mathematical Monthly, Vol. 20, No. 2 (1913)

“Precious Packages - America’s Postal Service” by the Smithsonian National Postal Museum

Direct quote.

Was it like an early version of Tide pods or the ice bucket challenge… but with children? I imagine this was certainly one way to get your 15 minutes of fame.

“Live Baby by Parcel Post,” The New York Times, February 1914

Some articles refer to her as Maud, not Maude.