#39: And as for you, don’t forget your Frieducha who adores you

Frida Kahlo's letters home

I’m waiting on a package from my mom.

When video chats and texts cross an ocean in a blink and we play Rummikub digitally on a whim, my mom and I spend time together almost as if the Atlantic, Georgia, Alabama, Missisippi, and Louisiana didn’t separate my Toulouse apartment from her house outside Houston.

That doesn’t stop us from sending snail mail all the time. When you live far apart, nothing compares to holding something your parent put into an envelope and mailed just for you.

Being able to video chat or text whenever I want undoubtedly made it easier for me to leave my family’s orbit and see the world. But if snail mail was all we had, how hard would it be to leave everything behind?

Twenty-three, chronically achin’, and wildly in love, Frida Kahlo did exactly that.

Today we’re talking about…

💌 Frida Kahlo’s relationship with her mama,

💌 Letters from San Francisco,

💌 Letters to New York,

💌 and the dark (and forgotten) history of Mexican Repatriation

🌺 Mother/Daughter // Loving/Giving

Search “Frida Kahlo” online, and most articles you’ll find dissect her relationships with men: her husband Diego Rivera, her lover and friend Leon Trotsky, her father and fellow artist photographer Guillermo Kahlo, and her doctor-turned-bff Dr. Leo Eloesser.

It’s not surprising. Even today, we often define women by the men in their lives, rather than their successes. Look at how folks refer to world-renowned international human rights lawyer Amal Clooney1.

But many women shaped Kahlo’s life, and not just titillating lovers like Georgia O’Keefe or Josephine Baker. One woman loved her from the day she was born: Matilde Calderón de Kahlo.

Over the years, biographers said that Kahlo had a strained relationship with her mother. But when a trove of letters donated to the National Museum of Women in the Arts were made public in 2007, their deep bond came to light.

It’s easy to see that they wouldn’t have always agreed with each other. Matilde was a conservative Catholic, loving yet set in her ideas of morality and the world2. Kahlo, on the other hand… was a polyamorous artist and leftist noted for her affairs with both men and women3.

But to conflate this combo of hardheaded daughter and traditional mother with a strained relationship is to do a disservice to the power of a family bond that transcends needing to “get” each other.

🌁 San Francisco: “The lights of Berkeley from their terrace”

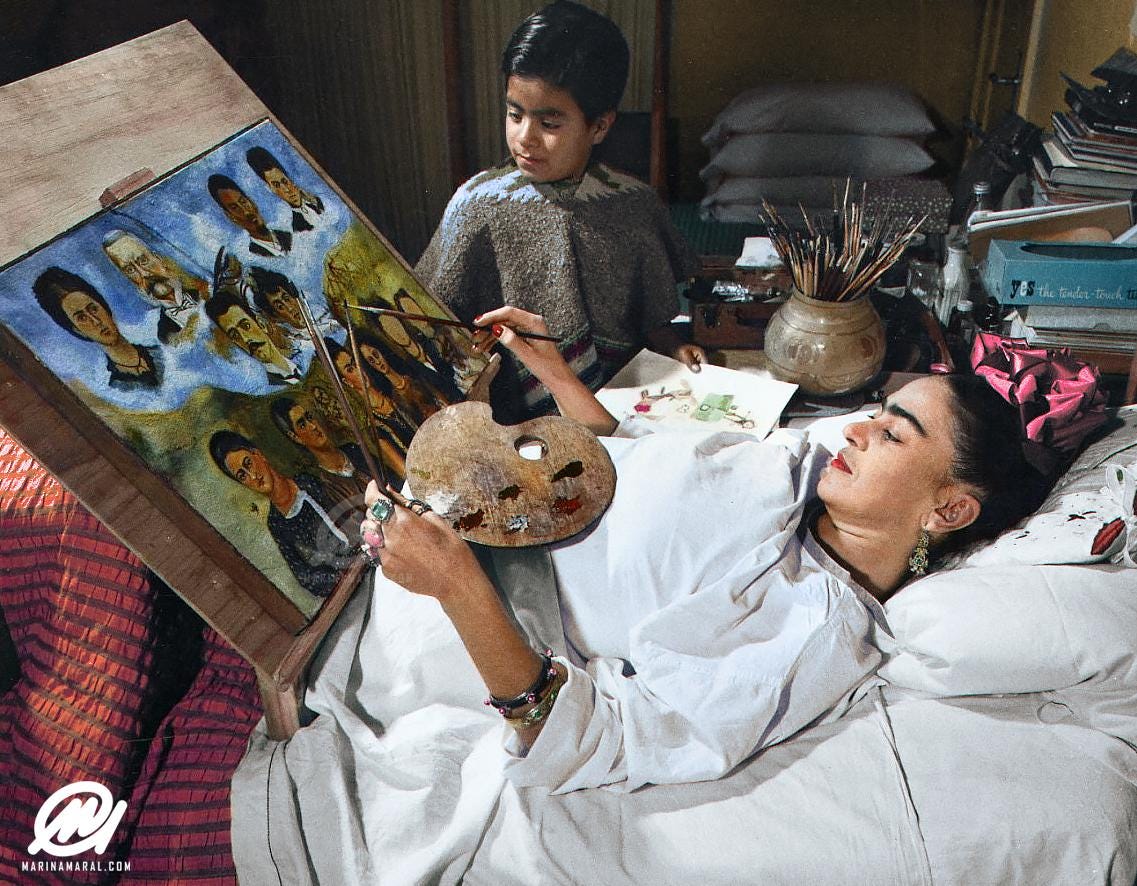

It’s 1931 and Frida Kahlo, 23 (same age as her mama in the pic above) has just left Mexico for the US4. Despite the Great Depression wreaking havoc, Kahlo’s husband Diego Rivera is undertaking mural commissions to beautify San Francisco.

As her husband works, Kahlo finds herself tumbling through a sea of fresh faces and free time in a foreign country, discovering her identity as an artist in her own right.

In this time of personal revolution, Frida Kahlo turns to her mother:

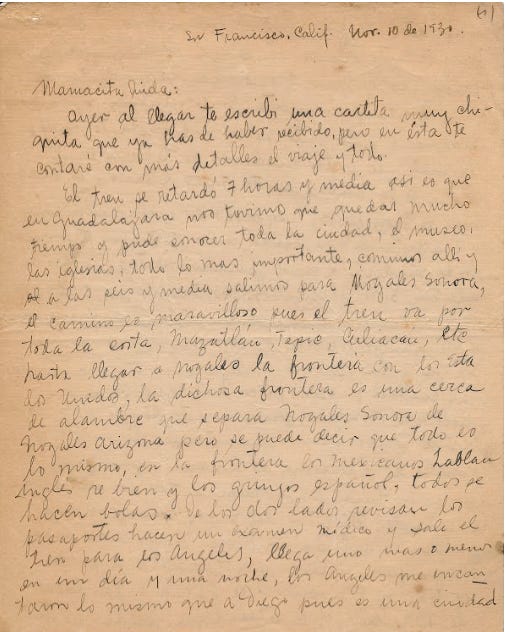

Mamacita linda,

Yesterday I wrote you a little letter when I arrived here. It was a very small letter and you should have received it by now…

The route is just spectacular. The train travels all along the coast… until it arrives at Nogales on the border with the United States. That famous border is just a wire fence separating Nogales-Sonora from Nogales-Arizona. But you could say that it’s all the same… They check passports on both sides… give you a medical exam and then the train leaves for Los Angeles…

I found Los Angeles exciting, as did Diego. Well, it’s a city in a marvelous location… The beach is magnificent, but the gringas look just horrible. The movie stars aren’t worth a Popsicle. Only rich people live in Los Angeles. The poor have a very hard life. Just imagine! A square meter of land in the center of the city costs 5,000 dollars, which is more than 10,000 pesos. The beautiful houses are only for multi-millionaires and movie stars. All the other houses are “pinchurrientas5” and made out of wood. There are 3,000 Mexicans living in Los Angeles. They have to work like mules to compete with gringo businesses.

Writing her mom two days in a row speaks volumes about their relationship, and I love how attuned she is to the difficulties facing L.A. residents right off the bat.

Frida goes on to describe her first day in San Francisco:

Yesterday afternoon, we were invited for cocktails at the home of the director of the Stock Exchange, where Diego is going to work6. They have a magnificent house and you can see all of San Francisco, the bay, and the lights of Berkeley… from their terrace…

I’m sending you one of the newspapers where they wrote about us. We have been in about six newspapers, but I haven’t been able to get copies of them all.

It’s so earnest to send newspapers to her mom :’). You think she knew back then that she’d become an icon?

She continues:

I’m writing this letter so poorly because I’m lying down. As usual, I’ve had some inflammation, but the wives of the other artists have been very good to me. One of them came and gave me a hot water bottle and the other… cleaned up the whole house. One is French and speaks Spanish. Her name is Ginette. The other one is a gringa, but she’s very friendly and a good kid.

We live very close to Chinatown. It’s almost around the corner. Chinese men and women go around as in the pictures wearing their authentic costumes. Up to now, I’ve only seen old Chinese women and children, and they are beautiful. I haven’t seen any young Chinese women. They sell wonderful things, beautiful robes and tons of other things. The loveliest here in general are the young children. They are enormous and beautiful…

Over time, Chinatown came to resonate with Kahlo greatly, influencing much of her fashion; she bought Chinatown silks and fabrics, styling them in ways that harkened back to her home.

But as any chronically achin’ human can tell you (hi), the beauty of travel only goes so far when you feel like shit. Affectionately calling her mom linda (beautiful) as she often did, Kahlo circled back to her health:

Linda: I’m suffering from so much inflammation that I haven’t gone out at all today. It must be the result of such a long trip.

Dr. Eloezer (sic) is coming to see me today… about my back problems… The doctor is very friendly. I met him yesterday. He speaks the old style of Spanish very well and he’s very intelligent. I’ll write you later to let you know how I’m getting along with him…

Never underestimate the power of a good first impression. Over the years, Dr. Leo Eloesser became one of Frida Kahlo’s closest confidantes7. A few years ago a trove of letters between the two was made public; endearingly, she addresses each one to Doctorcito Querido - dear little doctor. Eloesser did more than help her with her treatments; he was the one who encouraged Kahlo to reconcile with Rivera and remarry after their divorce in 1940, and helped her through the grief of a difficult miscarriage.

But Kahlo didn’t know she’d found chosen family in Dr. Eloesser yet. Missing home, she wrote,

I want to know every little thing you are doing, detail by detail…

Pet Shadow often and… As for the little yellow kitten, feed it more scraps than the others.

…Write to me often. You, more than anybody, know how much pleasure it gives me to receive letters from all of you, and especially from you. So don’t quit writing to me. I’ll write every day if I can. A thousand kisses to Papá, Kitty, la nena, and everybody. And for you all my love, your

–Frieducha–

P.S. Don’t be sad. Everything is going to be fine with me. Diego is very good to me and besides, I’m going to receive much better medical treatment here than I ever would in Mexico.

All that year, letters home churned, regular as clockwork. I love the everyday musings Kahlo sent her mom on February 12, 1931:

I tried to make the crepes, but they came out like “drunkards’ vomit.” I made a mess of turning them over, and they were raw in the middle. It’s useless for me to try to dedicate myself to cooking. I do it so poorly and I ruin everything. I think the best cause of action is to wait until I get back to Mexico and then you can teach me.

Before venting about how Mexican Americans are treated stateside, she then drops this chickie nug of information, as if she’s not about to become one of the most celebrated painters of the 20th century:

I’m painting. I’ve made six pictures and everyone has liked them very much.

The people from here have treated us very well. The Mexicans who live here in San Francisco are real mules. You can’t imagine. Anyway, there are idiots everywhere. And there are some gringos who, God help us, are as “thick as bricks.” But there are some positives. They aren’t as shameless here as they are in our beloved Mexico…

Misgivings about the US simmered throughout her letters and art. It makes sense. The Great Depression harbored violent anti-Mexican sentiment (more on that later) that cast a shadow over the warm reception she and Rivera enjoyed.

As always, Kahlo signs off with tender, if bossy, devotion:

Write to me from time to time. Don’t be mean. You can’t imagine the happiness that arrives with your letters…

Mamacita chula… Take good care of yourself. Don’t stay alone for long periods of time and be sure to go out and have fun on Sundays, even if it’s only at the grubby little movie house in town. Otherwise you’ll get too bored…

…meanwhile, your –Frieducha– sends you a million kisses.

🗽 NYC: “Central Park looks very pretty from here.”

Soon, Rivera finished his murals in San Francisco, and after a pitstop in Mexico, he and Kahlo headed on to New York City, baby!

Kahlo’s first letter to her mother simmers with disdain for upper crust society, especially compared to the hardships facing folks during the Great Depression. On November 23rd, 1931, she wrote her mom:

Every day has been a battle with old Lady Paine8, who’s been driving us nuts, along with her millionaire friends. But Diego and I just burst out laughing and we don’t pay any attention to her…

The Rockefellers invited us to lunch and dinner. The old man’s son is very intelligent and likeable, but, no matter what, one just can’t enter into this class of society, and as far as I’m concerned, I couldn’t care less…

It’s unbearably hot in New York. You’d think we were in Veracruz. One is constantly sweating, day and night, and since the houses and apartments have very little fresh air, it’s dreadful. One must also have the electric lights on all day because buildings don’t have access to daylight… because the very tall buildings don’t let in enough light.

…This hotel is good, but very expensive. We pay 175 dollars a month, but Diego prefers to pay a bit more rather than stay in some hovel far from where he’s painting and I agree.

And then, fulfilling every nosy person’s fantasy, Kahlo draws her mother a layout of their hotel/apartment:

As someone who’s lived in about 309 different housing arrangements, I often do this in my journals to remember what my home-at-the-time looked like, so this was a dream come true. She’s labeled everything, down to the radio. Looking at the map, you can picture her abandoning a half-finished letter on the desk to turn the radio on before perhaps ambling to the chairs overlooking Central Park.

Kahlo goes on to marvel at her own (atrocious) cooking skills again:

It’s on the 27th floor, so Central Park looks very pretty from here, and we have a little better air than other apartments do.

Inside the kitchen, the electric stove is wonderful. I don’t cook anything except breakfast. As you know, I’m a horrible cook. I make coffee and fried eggs, and we eat some fruit or gelatin or ham. This small breakfast costs about a dollar twenty five cents a day, which is about three Mexican pesos. One could eat a full day’s worth of meals for that in Mexico.I have lunch for fifty cents in a restaurant, and so far, we’ve been invited to eat out every night. Afterwards, I’ll just have to prepare the same thing as in the morning… Now, while I’m writing to you, I’m sitting next to the open window, so I won’t bake from the heat.

Well, Linda mía, don’t forget to tell me everything and to take very good care of yourself. Give thousands of kisses to Isoldita, give my greetings to Toño, and tell Kitty to write to me. Give Papá a kiss (when he’s in a good mood) and, as for you, don’t forget your Frieducha who adores you

–Frieda–

📞 The magic of the telephone

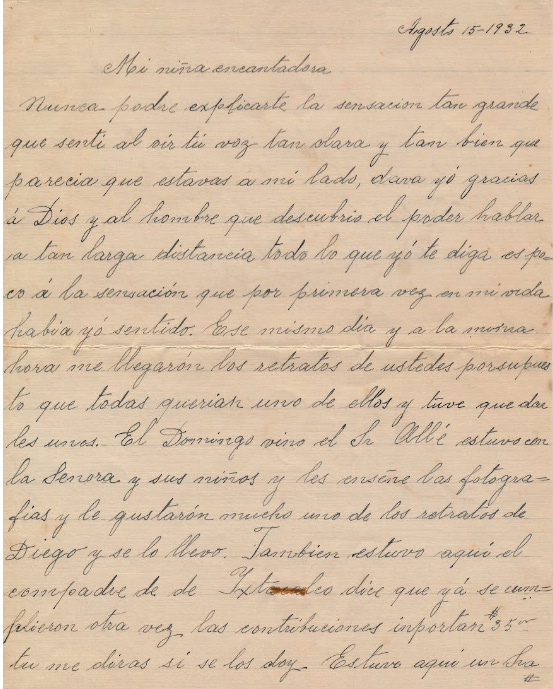

In 1932, Matilde Calderón de Kahlo was ill, her health rapidly declining. And in what may very well be the last letter Kahlo ever received from her, Matilde talked about a miracle we take for granted every day with such fervor it could break your heart:

The power of the telephone.

My charming little girl,

I’ll never be able to explain the wonderful sensation that I felt when I heard your voice so clearly and so well that it seemed as though you were right at my side. I gave thanks to God and to the man who discovered the power to speak over such a long distance. My words to you are nothing compared to the enormity of the feeling I experienced, for the first time in my life.

After sending this letter, Matilde’s health took a turn for the worst. Kahlo caught a frantic train back to Coyoacán to be by her side, arriving in early September to sit with her mother through those final days. On September 15th, 1932, one month to the day after their miracle phone call, Matilde Calderon de Kahlo died10.

At least Matilde had received the gift of her daughter’s voice one last time before her health declined.

“My words to you are nothing compared to the enormity of the feelings I experienced, for the first time in my life.”

A miracle.

🇲🇽 The Forgotten History of Mexican Repatriation

In the US in the 1930s, while Kahlo and Rivera painted their way across the country, shit was hard. Hoovervilles peppered the states, and a quarter of the working population couldn’t find jobs.

And as Kahlo and Rivera, two Mexicans, left their marks on the 20th century arts scene, police were rounding up and forcing the country’s Mexican Americans - both citizens and non-citizens - to Mexico.

From around 1930 to 1933, some 1.3 million Mexican Americans were exiled to Mexico. Sixty percent (that’s about 675,000 people) were U.S. citizens with Mexican ancestry, kicked out without legal precedent and sent to what was, for them, a foreign country.

Photographer Dorothea Lange interviewed and photographed Mexican American families at the time. In 1935, one mother summed up her kids’ identity well by saying,

"Sometimes I tell my children that I would like to go to Mexico, but they tell me, 'We don't want to go, we belong here.”

The deportation was unorganized and cruel. In raids, police would arrest crowds and force them onto trucks, buses, and trains heading south. On Olvera Street in Los Angeles, police once arrested over 400 people without cause, forced them onto flatbed trucks, and took them to Union Station, where armed guards pushed them onto a Mexico-bound train.

And according to one researcher, California State Senator Joe Dunn, most victims of this “repatriation” didn’t even speak Spanish fluently. These were Americans, exiled to a foreign country with no resources at their disposal11.

Technically, Hoover didn’t write this ethnic violence into law (states and cops did it on their own accord), but he did encourage it through his “American Jobs for Real Americans” campaign, as if American citizens of Mexican heritage are… less American than white folks?

The thing is, this forced expatriation actually withered the already broken economy. By forcing Mexican American residents, who mostly worked labor and farm jobs, out of their own country, white men faced job cuts by proxy: since there were less employees to manage, there were less managerial positions, and managers, administrators, and salesmen were out of work12.

1.3 million lives upended. That’s a third of the Mexican population in the United States at the time, many of whom had lived in those very lands since before it was considered the United States (see: the Mexican-American War)13.

When you hold that open hostility of the era in your mind, it’s easy to see why Frida Kahlo felt such strong antipathy towards the US upper crust, hesitating to embrace the gringas in her social circle.

The US government never formally apologized. And there’s a reason you’ve probably never heard of this era: in 2006, a survey combed through the nine most popular public school U.S. history books: from all nine combined, only four pages of material covered the repatriation, and only one book gave it more than half a page. Four of the books didn’t mention it at all14.

Sometimes history’s nasty, but the most radically beautiful and kind thing we can do is teach each other about it so we know how to treat each other better every dang day.

Write a letter home, talk to your friends about history (it’s important!), and above all, call a mom you love today.

Love forever,

Nikita, your Snail Mail Sweetheart

🚨 PS, Call to Action! 🚨

Tallahassee, Florida, where I grew up, was hit by the worst tornadoes in its history! It’s a hard time for the city, and the arts community’s beating heart, Railroad Square, was struck the hardest. It’s a series of art galleries, thrift stores, and all the things that make Tallahassee unique - and it’s in rough shape. If you can, please please please donate and help the local arts recover:

Share it far and wide - thank you!

I’m lukewarm at best on Tina Fey (Only Murders aside), but I do love this quote from when George Clooney was awarded the Cecil B. DeMille Lifetime Achievement award: “George Clooney married Amal Alamuddin this year. Amal is a human rights lawyer who worked on the Enron case, was an adviser to Kofi Annan regarding Syria, and was selected for a three-person UN commission investigating rules-of-war violations in the Gaza Strip. So tonight her husband is getting a lifetime achievement award."

LOL hi, mama! I love you soooo!

According to a translation from Google Arts & Culture, “pinchurrientas” is Mexican slang for “of the worst quality.” Tell me if you have a better translation tho, please!

You can go see “The Allegory of California” today.

The clickbaitily-titled “Frida Kahlo’s last secret revealed” by Javier Espinoza for The Guardian

Frances Flynn Paine, Diego Rivera’s agent.

For you nosykins out there, I just counted 37 places I lived in for at least three months where I had all of (or nearly all of) my belongings in tow. If I’m only considering spots that lasted at least six months, I clock over 25. Three of those included vans or campers, meaning despite considering my vehicles ~one location~, I woke up with a different view most mornings. France, please keep me still for at least a decade, thank you.

The Employment Effects of Mexican Repatriations: Evidence from the 1930’s (sic) by Jongkwan Lee, Giovanni Peri, and Vasil Yasenov for The National Bureau of Economic Research

This was a wonderful piece, Nikita. I read a biography on Frida years ago, so I'm a little familiar with her story, but I really enjoyed you taking the angle of highlighting her correspondence with her mom. My hat off to you.