#42: the corner of your mouth against my lips

The romance of the First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and Lorena Hickok

For someone that isn’t summer’s biggest fan (I burn if someone even says the word “sun”), there’s sure a lot to celebrate in June.

For starters, it’s Pride month, baby! In Toulouse, the parade snakes through main thoroughfares and we dance our way across the city behind floats, sharing makeup and reveling in each other’s looks and taking up sweet, glorious space for the whole dang city to see.

As of June, I’ve officially been in France for over a year. Last week, I picked up my latest visa to keep me in Toulouse’s arms til mid-2025.

June also holds Rhody and I’s anniversary - fourteen years! Time moves kinda like taffy on a pull machine when you’re in love. It feels like yesterday and like seven thousand years and like one week ago that our whole dang carousel of love began.

Maybe I’m in love with this newsletter, too, because time has flown. This month marks a whole dang year of Snail Mail Sweethearts. She’s undergone plenty of changes, but I still love everything we started in the early days, like my inaugural post (a now defunct theme, RIP) and my first microfiction.

And today, in honor of Snail Mail Sweethearts’ precious origins, we’re gonna revisit this bad boy’s first historical mail topic.

Today we’re talking about…

💌 the romance between Eleanor Roosevelt and Lorena Hickok,

💌 How Hickok lived in the White House with the Roosevelts,

💌 Their evolving romance and enduring bond,

💌 and the end of Prohibition and the (broken) promise of a more open society.

(An original version of this article appeared here.)

📰 Eleanor Roosevelt - queer icon?

When I first wrote about Eleanor Roosevelt and Lorena Hickok last year, I was in the throes of Queer History of the United States by Michael Bronski. It is one helluva read. Sometimes (and I say this as someone with a master’s in creative nonfiction), nonfiction books spit facts without worrying about hooking readers - but not this one. As I read, I found myself gasping at twists, laughing out loud, and swearing under my breath as Bronski revealed yet another queer twist to history.

One thing Bronski said in the forward stuck with me: we often separate history from queer history, as if they’re different tapestries. But the truth is, we’ve always been around; queer people have played active roles in the shaping of the United States (for better or worse) since its founding.

Eleanor Roosevelt is a prime - and rad - example. From her role in drafting The Universal Declaration of Human Rights to her protests against segregation laws in 1938, Eleanor Roosevelt arguably defined the role of First Lady for generations to come.

And she also happened to be in love with a woman.

Back then, being gay or lesbian wasn’t openly discussed, no never mind being bisexual. And while it might be nice to look backwards and slap a label onto historical giants, we have no way of knowing what they felt in their bones regarding their sexuality. But here’s what we do know without a doubt: Eleanor Roosevelt had lovers of different genders throughout her marriage to Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

FDR and Eleanor’s rather open marriage didn’t begin that way. Eleanor loved Franklin, but when she found out he was cheating on her with a secretary before he became president, she essentially told him, “Okay, rude, but it’ll ruin your career if we divorce and I support the shit out of your political ideology, so this is a loveless and sexless marriage for legit the rest of our lives. Cool?”

He said cool1, and they proceeded to have private relationships outside of their platonic marriage. Over the years, while Eleanor had affairs with men and women, none matched journalist Lorena Hickok - a great love of Eleanor Roosevelt’s life.

💝 A lifelong love

Historians can’t exactly pinpoint when Lorena Hickok, affectionately Hick, and Eleanor Roosevelt’s relationship went from friendly to fiery. Throughout Eleanor’s husband’s presidential campaign in 1932 and until mid 1933, Hickok was the personal reporter covering Eleanor Roosevelt. The two spent ample time together. Before her husband became president, Eleanor and Hick both lived in New York, where they spent nearly every day in each other’s company, going out to operas, enjoying one another’s company, and dining privately in Hick’s apartment often2. Sometime in that period is likely when the two got romantic.

And lucky us, throughout it all, these two kept up a fat correspondence.

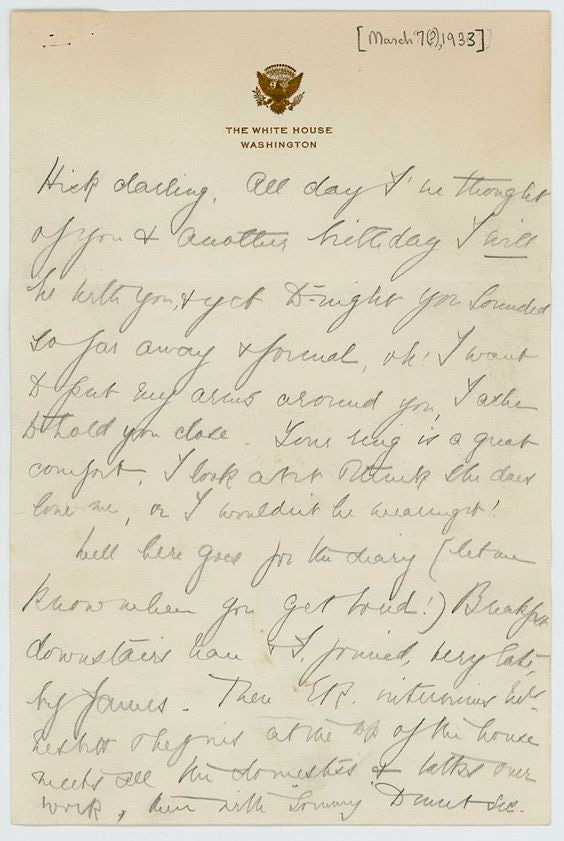

In early March 1933, Eleanor found herself in Washington, busy every day in the days leading up to her husband’s inauguration3 - so she kept herself close to Hick by writing daily letters:

Hick my dearest, I cannot go to bed tonight without a word to you. I felt a little as though a part of me was leaving to-night. You have grown so much to be a part of my life that it is empty without you even though I’m busy every minute.

These are strange days + very odd to me but I’ll remember the joys + try to plan pleasant things + count the days between our time together!

Imagine for a moment how it must’ve felt for Eleanor Roosevelt during the inauguration, standing beside the man who broke her heart with his infidelity, the man who remained someone she admired so much as a politician she stayed married to ensure his success. On one hand, she must have felt joy: a politician she supported bone-deep was in office during a time of turmoil - and she, in turn, would be able to wield his platform and make the country a better place, herself. On the other hand, never before had her life been under more scrutiny. Fresh in love with Hick, it must have been strange to suddenly be separated from her lover, every eye on the nation buttoned to her, as she stepped into a new era of the role of Wife.

Through it all, her and Hick’s relationship remained at the center of her thoughts. The next day she wrote to Hick again4:

Hick darling, Oh! how good it was to hear your voice, it was so inadequate to try & tell you what it meant, Jimmy5 was near & I couldn’t say ‘je t’aime et je t’adore’ as I longed to do but always remember I am saying it & that I go to sleep thinking of you & repeating our little saying.

Aaaand the next day, she followed up for good measure.

Hick darling, all day I’ve thought of you + another birthday6 [when] I will be with you, + yet to-night you sounded so far away + formal, oh! I want to put my arms around you. I want to hold you close. Your ring is a great comfort. I look at it and think she does love me, or I wouldn’t be wearing it!

After the inauguration, the Roosevelts acclimated to the tight scrutiny. In the new normal, Eleanor and Hick’s relationship escalated when Eleanor Roosevelt moved Hick into a room in the White House adjoining her own.

Even FDR seemed to be aware of their intimate relationship; how could he not be, when Hick lived with them and came to breakfast every morning?7

Eleanor and Hick’s fire kept burning bright. Eleanor, in her non-conventional marriage to her husband, had come into her own as what some folks consider the first First Lady to really put herself to work. She was too busy and too cool to give two licks about gossip, even if Hick was worried.

On November 27th, 1933, Eleanor wrote to Hick, addressing Hick’s concerns about folks’ prying eyes:

“Dear one, & so you think they gossip about us. Well they must at least think we stand separation rather well! I am always so much more optimistic than you are. I suppose because I care so little what ‘they’ say!”

There are very few letters from Hick to Eleanor (apparently she burnt them like any good secretive first lady might), but here’s this gem of queer yearning from Hick on December 5, 1933, musing over time spent apart:

Only eight more days. Twenty-four hours from now it will be only seven more — just a week! I’ve been trying today to bring back your face — to remember just how you look. Funny how even the dearest face will fade away in time. Most clearly I remember your eyes with a kind of teasing smile in them, and the feeling of that soft spot just northeast of the corner of your mouth against my lips. I wonder what we’ll do when we meet — what we’ll say. Well — I’m rather proud of us, aren’t you? I think we’ve done rather well.

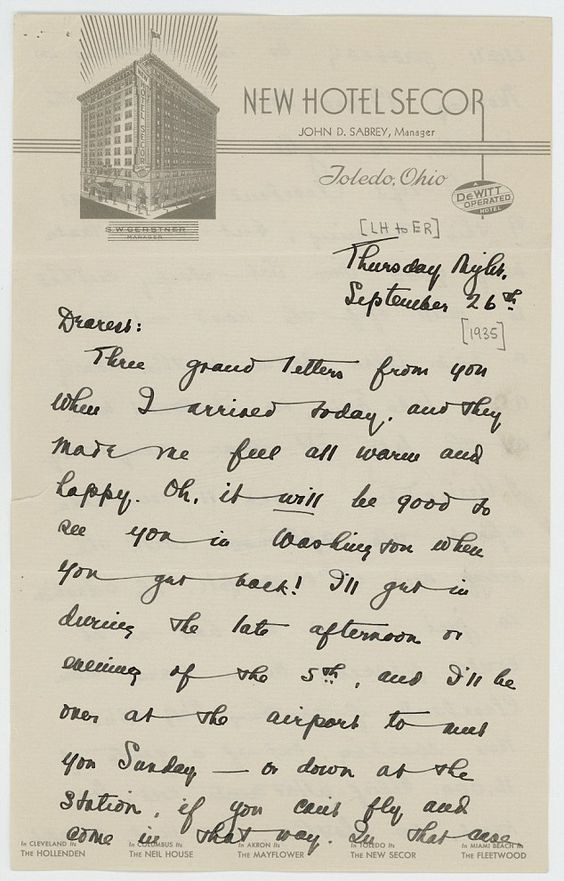

Y’all, they were in love. The fire kept going in 1935…

Dearest:

Three grand letters from you when I arrived today, and they made me feel all warm and happy. Oh, it will be good to see you in Washington when you get back! I’ll get in during the late afternoon or evening of the 5th, and I’ll be over at the airport to meet you Sunday - or down at the station, if you can’t fly and come in that way…”

Any of us who’ve been in love can relate, I’m sure, to the logistical backflipping Eleanor was doing to make sure she could see Hick at the literal soonest instant possible.

Over the years, their love changed - and in a way, it cooled. But one of the most beautiful things about queer love is how nebulous it is; the end of physical intimacy doesn’t mark the end of our deep and abiding love for former lovers. It’s not clear if there’s a definitive day Eleanor and Hick shifted to a more platonic iteration - and in fact, folks can’t agree on whether their love took a platonic bent ultimately at all - but they did begin spending more time apart. Possible reasons include WWII understandably taking up a lot of Eleanor’s time as First Lady and an activist. There’s also the fact that Eleanor harbored romantic feelings for her doctor, David Gurewitsch - although that interest was rumored to be unreciprocated.

Regardless of if they separated temporarily, permanently, or not at all, these two wrote romantically to each other for decades as their relationship took on different tones. By the end of Hickok’s life, she was living entirely on funding Roosevelt gave her. While there’s debate on whether their physical relationship sprung eternal, their love? There’s no doubt about it.

🏳️🌈 Queer folks have always been here

Queer people have been here since time immemorial. We have drafted treaties on human rights and founded universities and won Oscars and fought in the Civil War. We’ve been on the right and wrong side of US history (just ask some soldiers who fought for the Confederates). Queer people were royalty and farmers and boring-ass, regular people around the world since the dawn of time! And we’ll keep being all those things up until night falls on humankind (which I sincerely hope is a very long time from now).

🍻 Changing times, pour another round

So… what the frick was happening in the world in 1933?

The times were a’changin’. When FDR took office in 1933, the US was facing some dismal shit. Last month I talked to y’all about the forced removal of millions of U.S. citizens of Mexican descent between 1930-1933. The Roosevelts, progressives of the era, knew full well things needed to change.

But cooling their jets on the violent upheaval of Mexican-American lives wasn’t the only thing the Roosevelts had up their sleeves. They were committed to mending the very fabric of the country - and the mess that was Prohibition was one of them.

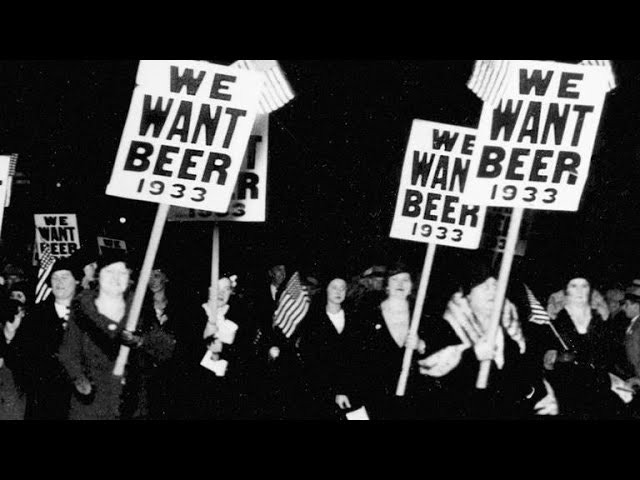

The 18th Amendment, signed into law in 1919, barred all boozin’ from the good ole land of the free. Its proponents had claimed all kinds of things to get it enacted: banning alcohol would end poverty, stop child abuse, and diminish violent crime. And obviously, advocates promised, it’d slash taxes, since less money would go towards almshouses, asylums, jails, and law enforcement.

But if something sounds too good to be true, folks, that means it is. Not only was Prohibition unpopular as hell, it didn’t actually do anything it promised. Interpreting data from the era is tricky and unreliable. Some sources point to crime and health issues decreasing, while other show that child abuse and violent crime actually increased when alcohol was illegal. Whether that’s because folks who drank in moderation missed their downtime glass of wine on the weekends or because folks were binge drinking illegal booze, it’s hard to say, but the fact remained that Prohibition wasn’t demonstrably effective in helping curb any societal woe.

One thing historians agree on across the board is that Prohibition didn’t save money; it cost the U.S. Government handily. Prohibition cut thousands of jobs - not just at breweries or distilleries; folks who made barrels and bottles and managed shipping lost work as well. Many restaurants and businesses shuttered, too, because they couldn’t make a profit without booze. And states that had relied heavily on alcohol taxes found themselves in a bind, the money they’d come to expect for meeting citizens’ needs now gone. All that tax revenue added up to $11 billion in losses during Prohibition - plus $300 million spent enforcing the amendment8.

As a fan of non-alcoholic beers and someone who doesn’t drink more than the occasional aperitif on a beautiful frickin’ day with buds (a shock to friends from my FSU and Moscow Party Demon days, I’m sure), I am not one to push a drink on anybody ever. But to criminalize something that has been part of human culture for at least 13,000 years9?

That’s about as dumb as criminalizing sexuality and forcing loving couples like Eleanor and Hick to sneak around. In fact, you can argue Prohibition is another chapter in the U.S.’ legacy of forced morality, where a group of people with their own personal thoughts on something - drinks, love, abortion - try to make it the law of the land.

For a country that has spent a few hundred years salivating over the separation of church and state, Prohibition was rooted in hypocrisy.

In my research, I came across an old article from Ohio State University in 1999 that makes this exact point. It’s a fascinating read because of the snapshot it provides of our recent history: Matthew Shepard’s torturer was on trial in Wyoming, and a growing distaste for homophobia was trickling into the U.S. mainstream. Suddenly, folks were drawing a comparison between homophobia and Prohibition, and realizing: hindsight never smiles favorably on enforced moral codes that undermine our autonomy.

In March 22, 1933, around the same time Eleanor was penning love letters to Hick, her husband signed the Cullen-Harrison Act into law, allowing for the sale of 3.2% beer and wine. Nine months later, on December 5th, 1933, the 21st Amendment was ratified, repealing the ban on booze and cementing booze rules where they belong: in people’s own dang homes.

It took until the Supreme Court case of Lawrence v. Texas in 2003 for queer intimacy to face the same decriminalization10.

Bonus material:

A Queer History of the United States by Michael Bronski - it is a fantastic read that spans from 1492 to the 1990s. I can’t recommend it enough!

Eleanor Roosevelt: First Lady of the World by Barbara A. Somervill.

If you wanna read all the letters (I know I do), there’s a whole book of them: Empty Without You, edited by Roger Streitmatter11.

This article from Mental Floss.

This article from NPR.

For anyone looking for an audio rendition of their letters, peep this tender experiment I found on Soundcloud:

I leave you now with this margarine commercial. Roosevelt used the money she received from this ad to send 6000 care packages around the world to folks in need.

If you had a good ride, the most powerful thing you can do is share this with a friend-o (or two).

All my <3,

Nikita, Snail Mail Sweethearts

I may or may not have paraphrased this conversation. Also, while this article completely strips Eleanor Roosevelt of her own sexual agency, it does have good references to FDR’s affair: ”No End of the Affair” by Charles McGrath

March 4th, 1933 was the final inauguration on that date before the Twentieth Amendment moved inauguration day to January 20th to shorten the lame duck period.

This article from Autostraddle.

Jimmy was her and FDR’s eldest son, who would have been fifteen when she wrote this letter.

March 7th was Hickok’s birthday.

“Straight matter?” I think not, sir.