#33: Fernando Pessoa, Pt. 1

The Portuguese poet with 75 faces

In an era of intense connectivity, we’re expected to answer texts and emails with a punctuality that would’ve made our ancestors’ heads spin. And when we’re not doing that, there’s always some bright, shiny terror on the news or social media to keep us hooked online.

When I’m dissociating on the couch, I like to look up and ask, “What would 1970s Nikita be doing?”

Sometimes, she’s listening to a record and drawing, sprawled on shag carpet. Other times, they’re at a disco, baptized in glitter. But mostly, she’s sitting at a typewriter, peering from behind oversized glasses and feathered hair.

Unfortunately, I am 2024 Nikita, a person who just finished her novel and now has to face the bleak-ass news cycle like everyone else without a grand project calling. Thankfully, like my peers, I’m a dang pro at dissociation. To avoid the fact that my novel’s done, this week I’ve thrown myself into DIY furniture remodel, binged sitcoms, gone to Meetups, hosted folks for wine, bought new pants (I hate pants shopping), rock climbed for the first time in half a decade, and devoured Molly Wizenberg’s memoir AND The Winternight Trilogy…for the second time. Basically, anything except, you know, writing for longer than twenty minutes.

1970s Nikita woulda panicked post novel, too. Maybe they’d watch TV, sitting through the commercials without getting up. Or binge fifteen romance novels from the library. Whatever she got up to, 1970s Nikita would at least have TV, friends a call away, and comic books to stave off self-awareness.

But how did someone juggling political strife and their artwork dissociate a hundred years ago? Maybe, just maybe, they’d conjure 75 alter egos to take over when the world became too much.

One guy, Fernando Pessoa, did exactly that.

And today we’re talking about Portugal’s beloved weirdo poet, covering…

💌 Fernando' Pessoa’s lonely upbringing

💌 some of his juiciest personas

💌 and what the heck was happening in Portugal in the first half of the 20th century.

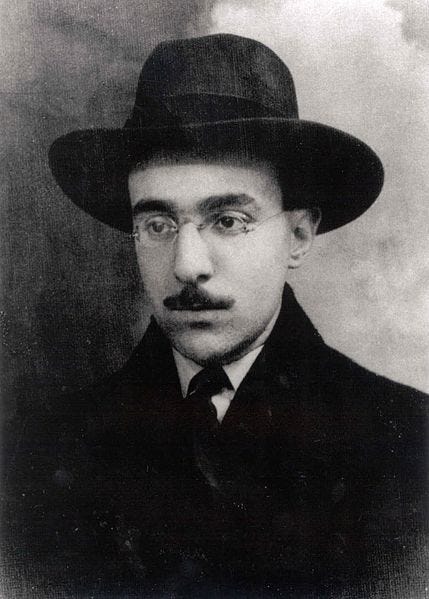

👥 Strangers within strangers within

An antisocial poet like Emily Dickinson, Fernando Pessoa wasn’t wildly known in his lifetime, and only became a national treasure posthumously. And like Emily, too, his transition from relative unknown to national celebrity seems to have stemmed from one thing:

Fernando Pessoa wrote a lot. A lot a lot.

Most scholars looking back on his life point to a few early tragedies that transformed him into this solo-flyin’ icon. In 1893, when Pessoa was five, his father died of tuberculosis, and a few months later, his baby brother followed.

Pessoa pointed to his father’s death as a primary defining moment, saying in a 1918 letter,

“There is only one event in the past which has both the definiteness and the importance required for rectification by direction; this is my father's death, which took place on 13 July 1893.“

I think all of us who lost a parent relatively young1 can point to the bisection of our lives. The two halves taste different. You never forget whether something happened in the “before” or the “after.” While five seems young, perhaps the death rattled him more because of what came next:

His mother and her new husband moved to what is now South Africa just two years later, little Fernando in tow. The rumor is that he wrote his first-ever poem when he learned they were moving. Worried his mother might leave him behind, he wrote2

Here I am in Portugal,

in the lands where I was born.

However much I love them,

I love you even more.To me, his fear of abandonment points to his self reliance from a young age, and an almost predetermined loneliness3.

Solitary doesn’t mean unhappy, though. Years later, he described himself as “an isolated child… quite content to be so,” Does that merry loner status conjures visions of Amélie for you, too?

In Pessoa’s eyes, he wasn’t exactly flying solo, anyway. And by the age of six, he counted among his friends someone who arguably changed his life: an imaginary dude named Chevalier de Pas. This dramatic French nobleman wrote Pessoa letters - letters Pessoa in fact wrote to himself.

Chevalier de Pas was part of a host of childhood characters who, Pessoa wrote, felt real to him, “fathomed to the depths of their souls.4” They were more than imaginary friends. So alive, in fact, that Pessoa said

“it requires some effort to realize they weren’t real5.”

In the company of Chevalier de Pas, Pessoa’s heteronyms were born.

🌊 A sea of personalities

“I unwind myself like a multicoloured skein, or I make string figures of myself, like those woven on spread fingers and passed from child to child… Then I turn over my hand and the figure changes. And I start over.6”

Lots of authors have pseudonyms. Stephen King fucked around and became Richard Bachman. JK Rowling has the laughable Robert Galbraith. Experimenting with your name to tackle a new style or theme is something writers have done for a long time.

But Pessoa didn’t have psuedonyms; he had heteronyms. Starting with Chevalier de Pas and continuing for the rest of his life, Pessoa developed around 75 (!) different personalities to write as. More than a pseudonym, these characters were distinct facets of himself, and Pessoa coined the term “heteronym” to convey that these personas were many parts of a whole.

Through them, Pessoa embodied different writing styles, political viewpoints, sexual orientations, ideologies, and habits. He published under these heteronyms, and they even interacted with one another, writing letters or reviewing each other’s work7.

And arguably, no heteronym was more critical than Alberto Caeiro.

Alberto Caeiro

A rural poet whose education ended at primary school, Alberto Caeiro’s upbringing couldn’t be more different from Pessoa’s international childhood and Lisbon roots. Caeiro’s life was short - born in 1889, the year after Pessoa, he died of TB in 1915 - but his fictional time on earth impacted Pessoa and his other heteronyms deeply8.

Like Pessoa, Caeiro was a neopagan poet and a core member of what Pessoa called the “General Program of Portuguese Neo-Paganism.” However, unlike Pessoa, Caeiro was a born leader, teaching acolytes including heteronyms Álvaro de Campos, Ricardo Reis, António Mora - and Fernando Pessoa himself.

António Mora, who called Caeiro “the New Pan,” once wrote this about Caeiro and his impact on neopaganism:

In order for paganism to be reborn, a pagan needed to appear, a man with a pagan mind, who could spontaneously reveal that pagan sensibility for others to adapt…

If Destiny wanted that to be so, then it would be. And Destiny did.

Alberto Caeiro appeared9.

Remember, all of these names are characters within Pessoa himself. Take a second and picture him sitting at a desk, drink at his elbow, embodying Mora and thinking about fellow heteronym Caeiro, Pessoa’s own personality not factoring into the equation at all.

Pessoa was fluent in English, while Caeiro’s work was exclusively in Portuguese. Writing as Pessoa, he once drafted a fictionalized review and translation of Caeiro’s work for English audiences10:

In placing before the English-reading public my translation of these poems, I do so with the full confidence that I am making a revelation. I claim, in all confidence, that I am putting before Englishmen the most original poetry that our young century as yet produced – a poetry so fresh, so new, unattained to such a degree by any kind of conventional attitude, that the words a Portuguese friend said to me, when speaking of these very poems, are more than justified. “Every time I read them”, he said, “I cannot bring myself to believe that they have been written. It is so impossible an achievement…!”

…Alberto Caeiro – that is not his whole name, for 2 names are suppressed – was born in Lisbon in August 1887. He died in Lisbon in January of the past year.

You gotta wonder about the “friend” referenced in this letter; is he another heteronym, or someone flesh and blood? And Caeiros’s suppressed middle names make me laugh; the personal detail adds heft to Pessoa’s dynamic inner world.

The most famous work attributed to Caeiro was The Keeper of the Sheep, a collection of 49 poems that Pessoa edited until his death in 193511.

Short though his life was, the heteronym Alberto Caeiro’s devotion to the occult and poetry changed the trajectory of the rest of Pessoa and his heteronyms’ lives.

Alvaro de Campos

Despite being a devotee of Caeiro, heteronym Alvaro de Campos’ disposition couldn’t be more different from Caeiro’s easygoing, pastoral view.

Campos was every nostalgic and sad boi part of Pessoa, wrapped up into one Whitman-obsessed poet, writing lines like…

I'm nothing.

I'll always be nothing.

I can't want to be something.

I have in me all the dreams of the world nevertheless.Despite the difference in temperament, Campos loved Caeiro. In this letter, “Notas para a recordação do meu mestre Caeiro” (notes to remember my teacher Caeiro”) Campos acknowledged their differences:

My master Caeiro was not a pagan: he was paganism. Ricardo Reis is a pagan, Antonio Mora is a pagan, I am a pagan; Fernando Pessoa himself would be a pagan, if he weren't a ball wrapped inside.

But Ricardo Reis is a pagan by character, António Mora is a pagan by intelligence, I am a pagan by revolt, that is, by temperament. In Caeiro there was no explanation for paganism; there was consubstantiation12.

Campos loved to question the concept of Fernando Pessoa, once writing, “curious is the case of Fernando Pessoa, who doesn’t exist, strictly speaking.“

Nonexistent or not, Pessoa kept track of all the heteronyms with ease. But although Pessoa distinguished one from the other, he realized other folks might not keep them straight so easily. In 1935, not long before his death, Pessoa wrote a letter to fellow Portuguese poet Adolfo Casais Monteiro, outlining his characters’ backgrounds and personalities:

“[Campos was] born in Tavira, on October 15th, 1890 (at 1:30 p.m., says Ferreira Gomes, and it’s true, because a horoscope made for that hour confirms it). Campos…is a naval engineer (he studied in Glasgow) but is currently living in Lisbon and not working13.”

Aaaand here’s the astro chart in question, drawn by Pessoa in 1917:

Maybe Campos was an embodiment of the turbulence Pessoa felt inside. By becoming someone else entirely, this man who feared his mother’s rejection, who lost his father young, who died of alcoholism before the age of 40, could probe the depths of grief.

Maria José

With over seventy heteronyms to unpack (like Bernardo Soares, who wrote parts of Pessoa’s posthumous masterpiece The Book of Disquiet) it’s hard to condense Pessoa’s life down to a handful of heteronyms.

But at Snail Mail Sweethearts, we live for the letters, baby. And that’s why lesser-known heteronym Maria José caught my eye.

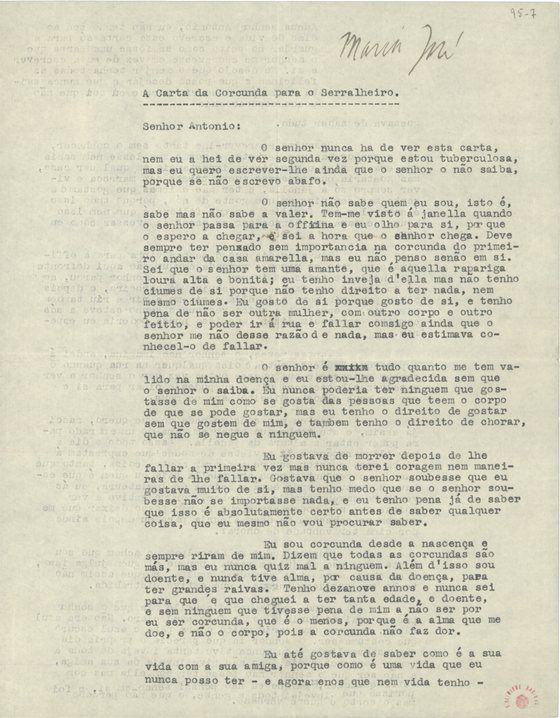

Nestled among thousands of pages discovered after his death was a letter he’d written as Maria José14, a teen with a spinal disorder and tuberculosis who apparently had the hots bad for a metal worker named Antonio. Self-conscious about her appearance, she wielded words instead of showing her face:

Mr. Antonio,

You will never see this letter, nor will I see it a second time because I have tuberculosis, but I want to write to you whether or not you ever know, because if I don’t write I’ll be stifled.

You don’t know who I am, that is, you know but you really don’t know. You’ve seen me at the window when you go to the workshop and I look at you, because I wait for you to arrive… I know you have a lover, who is that tall, beautiful blond girl; I’m jealous of her, but I’m not jealous of you…

What I love about this letter is the yearning. Pessoa is only known to have had one romantic relationship, an affair with a woman named Ofélia Queiróz. But his characters often talk about yearning and love and, in the case of Campos, bisexuality.

Even in this simple letter written as Maria José, Pessoa lost himself (found himself) in the notion of being someone else.

But a man so dang passionate about being everyone but himself begs the question…

🌍 What was happening in Pessoa’s world?

The first quarter of the 20th century was a dark time for Europe and Africa both. The First World War introduced trench warfare and mustard gas. Portugal was at the forefront of a violent and hostile occupation across Africa15. The Great Flu of 1918, starting in Western Europe where Pessoa lived, killed millions of people worldwide.

In short, shit was fucked when Pessoa came into consciousness. The entire arts movement in the west was choking on the conviction that nothing mattered - just ask the Dadists and e.e. cummings.

Portugal in particular was upside down. In 1908, three years after Pessoa left South Africa and returned to Lisbon, Portugal’s King Charles and his heir were assassinated in the city streets. And at just twenty years old, Pessoa witnessed his hometown falter under political upheaval.

By 1910, the monarchy was kaput, Catholicism wasn’t enforced as the lay of the land, and a provisional government had taken its place. There was voting (kinda) for a handful of adult men. From what I understand, the idea of liberty and a democracy was toyed with, but not doled out in full.

Cue the disillusionment, folks. And before the average Joes of Portugal could catch a break, an authoritarian military regime took hold in 1917’s bloody coup, sparking a civil war.

This was around the time that Pessoa first invented Caeiro and his simpler, rural life. It’s easy to imagine Pessoa then, stuck in a Lisbon dripping with violence and suspicion, happily disappearing into Caeiro’s neopagan embrace.

I wish I could say things got better for Portuguese citizens, but they didn’t. By 1926, fascism had the country in its grip. And the far right’s stranglehold on Portuguese freedom of expression likely has a helluva lot to do with why Pessoa displaced his more freewheeling views - bisexuality16, paganism, rebellion - into characters like Campos. It was safer for someone else to want those things.

Pessoa painted himself as a man uninterested in politics17. In The Book of Disquiet, he wrote that “all revolutionaries are as stupid as all reformers,” a sentiment that plays out in his short story “The Anarchist Banker.”

If the uncertainty of his time rings achingly familiar, I get you. Today we’re still nursing wounds from a global pandemic, fascism is indeed on the rise, and a genocide is currently raging. While I don’t know anyone alive right now wielding heteronyms, I definitely know people who present joy and light online, then dissociate on the couch. I also know folks (and am one of those folks) who, when the pressure of the world outside wants to snap me in two, disappear into video games, creating a character with interests and outfits and objectives completely unlike our own, all to feel something else for a few hours.

A hundred years apart, to me, Pessoa’s love of heteronyms reflects our own souls in the modern era, fighting to escape our skin.

In his lifetime, Pessoa only published 4 small poetry collections, and most of his writing ventures and magazines were, from a capitalist standpoint, failures. But Pessoa himself, in all his dissociating delight, was far from a failure; after his passing, people discovered a trunk in his apartment stuffed with 30,000 pages of poems, prose, and fictitious letters.

And if showing up for your writing - and all seventy-five temperaments you contain - in the face of global uncertainty isn’t success, then hot damn, I don’t know what is.

All my love and stamps forever,

Nikita, Your Snail Mail Sweetheart

IMO, “relatively young” is under 35 re: losing a parent. It’s young enough where you’re mostly alone in a sea of peers who have both parents still kicking.

Transcription, context, and image courtesy of the Modernismo archives.

I’m shuddering at the idea of picking at a project for 21 years!

If you haven’t read about the atrocity that was The Berlin Conference, I highly recommend you do! It informs so much of African politics to this day.

Y’all know I’m a sucker for chaotic bisexuals, and hoo boy does Pessoa fit the bill or what?

![[Carta a Adolfo Casais Monteiro] [Carta a Adolfo Casais Monteiro]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!r_s5!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4050b75e-f2d2-4319-bade-fab9976d6659_600x764.jpeg)