#30: Wild Nights - Emily Dickinson and Sue Gilbert's decades-long love

neighborly snail mail, spicy poems, and Victorian sexuality

The past 2+ months I’ve been off Instagram, and by and large, it’s ruled. But this week I discovered a drawback to the whole hiatus thing when I popped on via computer and found a missed DM from December announcing that my latest short story has been published in The New Orleans Review!

I’ve waited 9 months for it to make its debut, but “The Last Great Artist of Moscow” is out in the world and I couldn’t be prouder. Pop over and give it a read if you like sad clowns and petty main characters.

This magazine is the most ~prestigious~ of my career so far (eee!). It’s surreal as hell to see my name in the same issue as a reprint of the magazine’s interview with James Baldwin. As I write this, I’m at my dining table, staring at a 2’x 3’ painting I made of him a few years back. Life is weird.

I’d planned on announcing other writing news in this issue, so y’all get a double whammy. Since December, I’ve been working on a zine of all the short stories I wrote for Snail Mail Sweethearts last year. Now, after 304599 hours editing them, the stories’ final drafts are published in my very first zine, featuring hand-drawn illustrations! Printed copies are already in envelopes for my patrons. Nab an electronic version or a physical copy here, or join the postcard club to get one sent your way. I’ve wanted to make a zine since I was 13 or 14 and shouting along to “Carnival” by Bikini Kill in my bedroom, so it’s a lil teenage dream come true.

Honesty time: 20 years ago, when I was a goth dumpling sweating my way through fishnet arm stockings and a half-inch ring of eyeliner in the deep south, I was not an Emily Dickinson fan. School taught us about a poet so meek, so mousy, everything a lady “should” be. Certainly nothing my combat-boot-stomping self could get behind.

Hoo doggie, did I have it wrong. Emily Dickinson was cool. And it turns out, sexual repression and McCarthyism are to blame for the misrepresentation.

So let’s chow down on the true story of Emily Dickinson’s wild love by talking about…

💌 The sweet beginnings of Emily and her lady Sue,

💌 Hundreds of letters and decades of love,

💌 Her other lovers (our girl was fiery),

💌 Victorian sexuality,

💌 & how Emily Dickinson got rebranded into a pious little

spinster recluse.Let’s get to it!

❤️🔥 A tavern keeper’s daughter and a weirdo poet fall in love

Literally referred to as “The Myth” in her day, Emily Dickinson was no doubt weird. She wore only white, wrote constantly, and quit going to church early in life (a big deal for those days). She only cared about what folks thought about her poetry, which is why it’s crushing to realize less than twenty of her 1800+ poems were accepted for publication during her lifetime.

In 1850, when Emily was just twenty years old, a woman came crashing into the Dickinson family orbit, knocking everything from alignment that Emily and her brother Austin had ever known before.

Her name was Susan Gilbert.

The siblings were smitten. Susan - affectionately Sue - was the daughter of a tavern keeper and quickly won both Emily and Austin’s hearts. But Austin couldn’t compete with the tempest that was Emily. Passionate and creative, Emily captivated Sue. The two women spent nearly every moment together - and they fell hard. Sometime in those first months, their relationship turned romantic. They would secret away on private walks, savoring their stretches of alone time.

Even when Sue - always ambitious - left for a job as a schoolteacher in Baltimore, and later headed west for another position, their ardor endured via snail mail. The post carried Emily’s love to Sue wherever she went. Here’s Emily looking forward to Sue’s next visit:

Susie, will you indeed come home next Saturday, and be my own again, and kiss me ... I hope for you so much, and feel so eager for you, feel that I cannot wait, feel that now I must have you—that the expectation once more to see your face again, makes me feel hot and feverish, and my heart beats so fast ... my darling, so near I seem to you, that I disdain this pen, and wait for a warmer language.

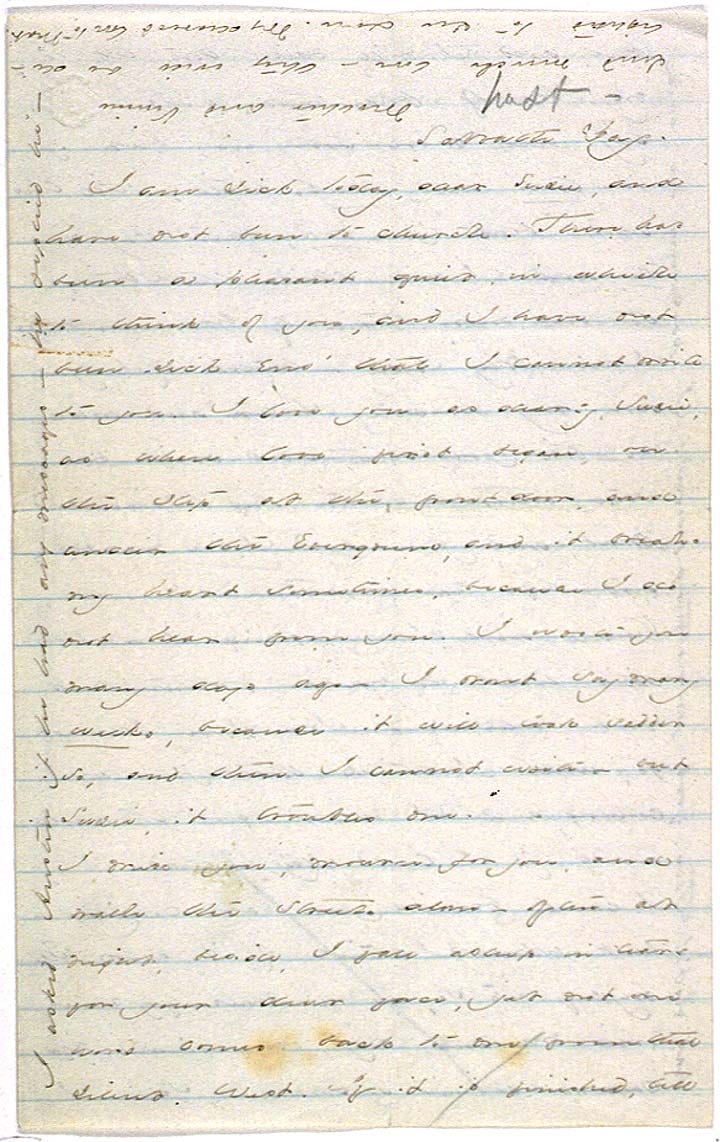

If you’ve read her poetry, you know Emily Dickinson was the kind of person with so many thoughts coursing through her, ideas and poetry weaseled their way into the mundane; many of her poems were written on the other side of recipes1. In the letter below, her thoughts run so slapdash, she crammed notes in the margins and upside down on the page while telling Sue she was afraid that she loved Sue more than Sue loved her:

…I love you as dearly, Susie, as when love first began, on the step at the front door, and under the Evergreens2, and it breaks my heart sometimes, because I do not hear from you. I wrote you many days ago I wont say many weeks, because it will look sadder so, and then I cannot write but Susie, it troubles me.

I miss you, mourn for you, and walk the Streets alone often at night, beside, I fall asleep in tears, for your dear face, yet not one word comes back to me from that silent West. If it is finished, tell me, and I will raise the lid to my box of Phantoms, and lay one more love in; but if it lives and beats still, still lives and beats for me, then say me so, and I will strike the strings to one more strain of happiness before I die.3

History’s icons often feel larger than life, but this letter grabs you by the shoulders and shouts that Emily and Sue were real people. The evergreens and the front step are so specific, referring to concrete exchanges and secret intimacies Sue would no doubt recall as soon as she read the letter. Did they kiss hidden in the trees? Did they hold hands on that front porch step?

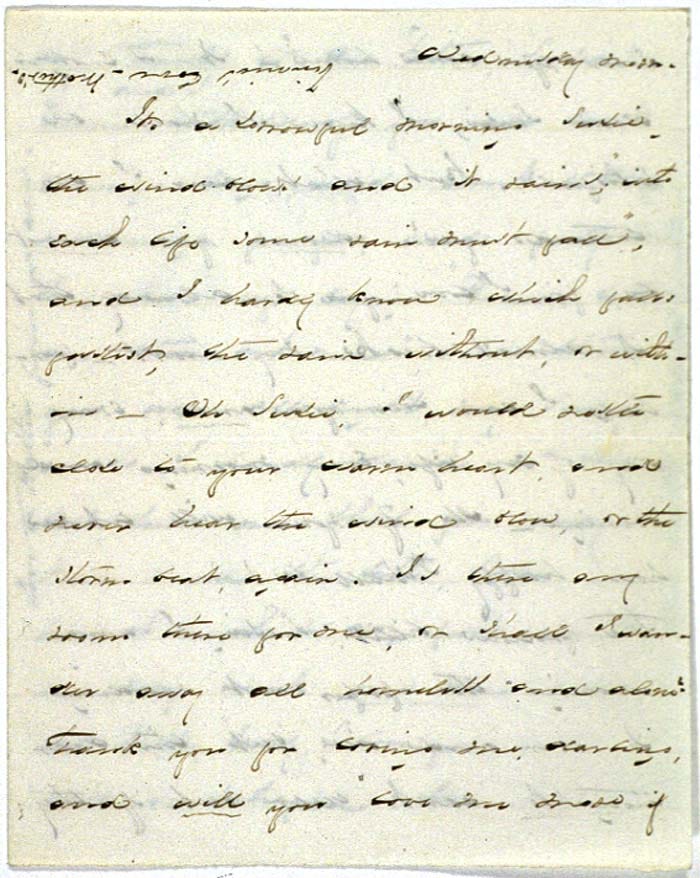

Emily addresses her fears to Sue again during that separation:

…Oh Susie, I would nestle close to your warm heart, and never hear the wind blow, or the storm beat, again. Is there any room there for me, or shall I wander away all homeless and alone? Thank you for loving me, darling, and will you "love me more if ever you come home" !

…dearer you cannot be, for I love you so already, that it almost breaks my heart - perhaps I can love you anew, every day of my life, every morning and evening - Oh if you will let me, how happy I shall be…

Never mind the letter, Susie; you have so much to do; just write me every week one line, and let it be, "Emily, I love you," and I will be satisfied!4

As it turned out, Emily had at least some reason to be worried.

💍 A (failure of a) marriage

When Susan came back from her teaching stint out west in 1856, she dropped a bomb: Sue was marrying Austin. Emily’s brother.

Glancing backwards, we’ll never know what motivated Susan to marry Austin, but we do know her salary as a schoolteacher wouldn’t have let her live independently; staying unmarried wasn’t a choice she could make. One working theory is that Sue married Austin so she could stay close to Emily.

But even if that were the case, Emily was gutted, and didn’t attend the wedding.

Ultimately though, true love doesn’t let details like brothers stand in the way! Over the years, Emily’s grief waned, and her and Sue’s romance kept burning true. Next-door neighbors for the rest of their lives, hundreds of poems and letters passed between them over the decades. Sue coined the phrase “letter poems” to describe Emily’s chaotic missives. And, being the hecka extra queer that she was, Emily sometimes made the dramatic choice to send them via mail instead of walking the short path joining their houses.

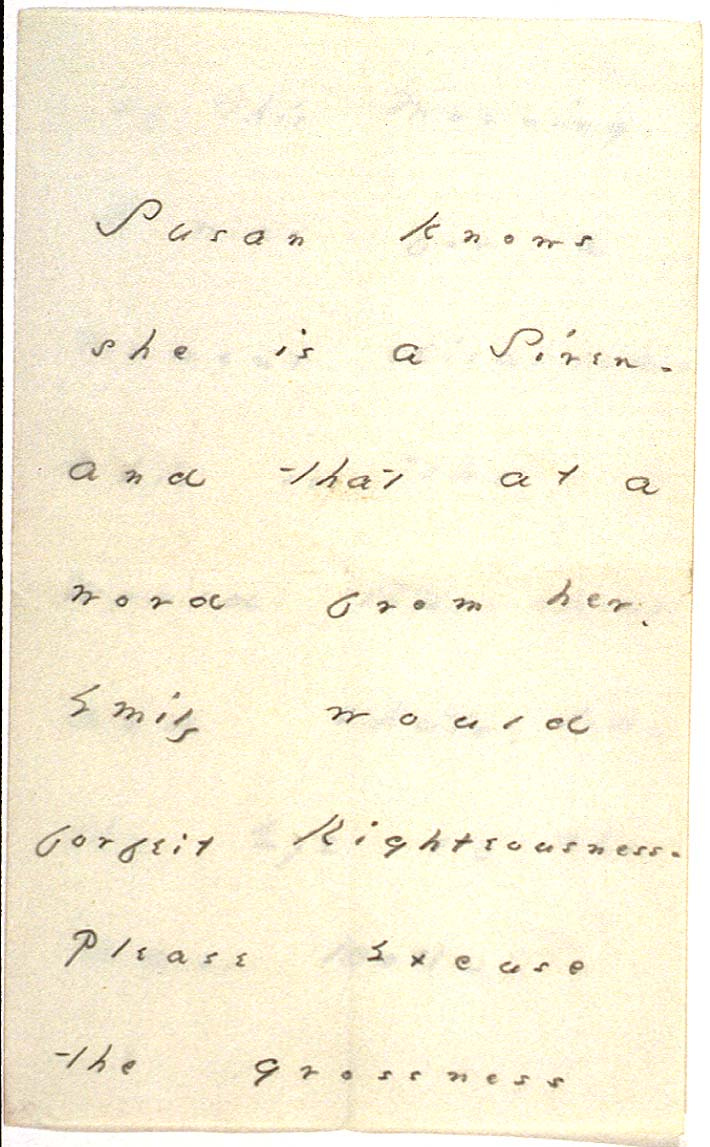

One of my favorites:

Susan knows

she is a Siren -

and that at a

word from her,

Emily would

forfeit Righteousness -

Please excuse

the grossness

of this Morning

I was for a

moment disarmed -

This is the

World that opens

and shuts, like

the Eye of the

Wax DollWhat I love about this letter poem5 is how much it packs into so few words. Her apology for “the grossness of this Morning” offers us a glimpse into their everyday lives together - even the ugly or petty parts.

But not everything she wrote was about conflict. Sometimes, Emily got spicy6:

Wild nights - Wild nights! Were I with thee Wild nights should be Our luxury! Futile - the winds - To a Heart in port - Done with the Compass - Done with the Chart! Rowing in Eden - Ah - the Sea! Might I but moor - tonight - In thee!

If you had your doubts about her and Sue’s relationship, rest assured there ain’t nothing platonic about asking to moor in someone for a wild night.

Molly Shannon’s brilliant portrayal of Emily Dickinson in Wild Nights with Emily paints a way more accurate picture of Emily and Sue than what we learned in school:

Could you blame Emily’s brother for eventually finding love outside his marriage with his mistress Mabel Loomis Todd? You can’t exactly compete with the intensity of Emily.

💐 Keepin’ busy

Look, if Susan could have a husband and Austin could have both Susan as his wife and a mistress on the side, why couldn’t Emily have other lovers, too?

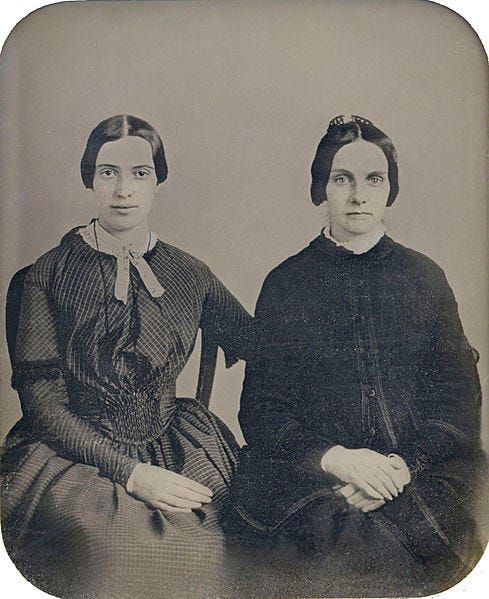

In brief stretches, Emily explored other relationships, too. The photo below is (probably) the second known photo of Emily Dickinson. While the person on the right is certainly one Kate Anthon (Emily’s temporary flame and Sue’s lifelong friend), it’s not verified for sure that the person on the left is our Emily7. The resemblance, however, is spot on, and the timeline syncs up with when the two were an alleged item:

From about 1859 to 1862, these two had a thing going. Many historians, like Rebecca Patterson, think they were far more than friends. Kate Anthon was well known for her queerness. And when you pair that with Emily knitting Kate a pair of garters and sending her this poem…the truth speaks for itself:

When Katie walks, this simple pair accompany her side,

When Katie runs unwearied they follow on the road,

When Katie kneels, their loving hands still clasp her pious knee —

Ah! Katie! Smile at Fortune, with two so knit to thee!8

Do straight people knit each other garters? I can’t say. But I can say I’ve only ever thought about other people’s garters in a fruity way.

Emily also had at least one documented emotional, and possibly physical, affair with a man. Late in life, she shared passionate correspondence with a man named Lord, one of her father’s friends. Their letters get spicy (for the time) with direct references to thinking of him intimately9. He pressed her for marriage, which she continually declined, until his death in 188410.

While her love for him never matched what she had for Sue, there’s no denying the power in her yearning:

“It is strange that I miss you at night so much when I was never with you –“

All these other lovers got me thinking…

🍑 WTF was sexuality in the Victorian era?

It’s easy to look back on the past with our 2024 lens and try to apply labels that make sense to us today. But when you consider that we the term “bisexuality” didn’t even exist until 1892 (six years after Emily Dickinson died), I don’t think there’s a way to look at her love affairs without our own sensibilities clouding our understanding.

I think that’s the hardest thing about studying social history, especially as a writer (just ask my novel, which is set in 1959 and written by a fictional author in 1973, while me, the real author, is polishing it in 2024; the logistics are a minor mind-fuck). We can’t help but apply our own understanding of sex, gender, and societal norms onto the past. Maybe Emily didn’t spend much time puzzling over her sexual identity. Maybe she would have labeled herself largely Sue-sexual. Maybe (probably) she would have thought labels are dumb.

We’ll never know. But here’s what we do know about the time era Emily and Sue loved one another in11:

💞 Homosocial society, romantic friendships: In Emily's lifetime, society was largely divided along gender binary lines. Women socialized with women, men socialized with men (and don’t you dare step outside those two options). Friendships often took romantic turns, even if they weren't sexual. In women's colleges, for instance, freshman girls would court the older girls, giving them gifts and locks of hair. An older student who got courted by a younger one was referred to as getting "crushed" - as in, a good ole fashioned crush.

💞 Boston Marriages: From about 1870 to 1920, some women relished a golden window of independence. Some wealthier or educated women, rather than marrying a man, arranged themselves into what were called “Boston” or “Wellesleyan” marriages where they "married" other women. These women shared a home and could keep their jobs without the pressure of having to become a homemaker. Sometimes, these were genuinely platonic arrangements between friends, but other times, they were hella gay (see below).

💞 Financial dependence on men: Here’s the thing about the utopia of a Boston marriage: they only worked for women who had the financial means to be independent, like women’s college scholars or rich heiresses. Regular women like Emily and Sue wouldn’t have had that luxury, especially when you consider that Sue was already married with children when the Boston Marriage became popular.

🌫 Emily Dickinson - the Myth, made

After Emily died in 1886, her brother’s married mistress (monogamy and this family didn’t gel, y’all), Mabel Loomis Todd, published Emily’s poems - after some questionable edits. Wanting to make a buck rather than ruffle feathers, Mabel erased any references to queer affection, going so far as to rewrite names and pronouns so love poems referred to men. A 1998 New York Times article revealed that infrared technology showed Susan’s name had been erased from some of the more longing poems and letters.

Not satisfied with the rewrite, Mabel took things a step further, establishing the myth of Emily as a troubled recluse, giving us the austere image folks hold onto today.

But Sue’s daughter Martha fought back against the misrepresentation. After her mother’s death in 1913, Martha Dickinson Biachi published a compendium of Emily’s correspondence, keeping original names and pronouns in all the work. Maybe because her mother died, Martha thought it was time to share the gay stuff without worrying about Sue’s social standing. Martha also shared many stories about Emily, challenging the notion of her as a recluse, instead painting a picture of a queer, loving, vibrant homebody.

Unfortunately, Todd’s rendition proved more palatable for prudes, and the spinster recluse lies took root.

In 1951, Rebecca Patterson challenged that notion again with her book The Riddle of Emily Dickinson, which detailed evidence of Kate Anthon and Emily’s affair. Finally, Emily’s truth was gaining traction.

The problem? McCarthyism and The Lavender Scare. In an era when folks were fired for even a whiff of the gay, it’s no surprise that the idea of a treasured American poet being a lady-smoochin’ wild card freaked people out.

In retaliation against Patterson’s book, scholars doubled down on the recluse angle, afraid Dickinson’s work would be pulled from schools to not corrupt the youth (does this sound painfully familiar? Anyone else getting a case of the oh-dang-Florida shivers?).12

However, truth has a way of wriggling free. It’s taken over a century for people to start acknowledging Emily and Sue’s wild-bright love, but the convo is shifting. So much time has passed, we’ll never know the intimate details that brought each letter to life, but we’ll do our best to piece it together and honor their love.

In a way, maybe our new stories about Sue and Emily mirror Emily’s own words on how to tell it like it is:

Tell all the truth

but tell it slant –

See you next week!

Because this is a short month, I’ll send out voting time a few days early. Keep an eye out! We’ll return to our every-ten-days schedule in March.

In the meantime, all my love and Emily-Dickinson slant truth,

Nikita, Your Snail Mail Sweetheart

PS, want more? Read the microfiction and peep the sapphic postcards now:

#32: the cat gets the cream

Two weeks ago, Rhody and I applied to renew our visas for another year here in France. Yesterday I cafe hopped and “co-worked” (read: talked and drank coffee) with my friend and fellow writer Ally. The coffee was strong and the sky got so blue as the day wore on. On the way home, I stopped for a glorious loaf of bread before biking down quiet side stree…

Emily was a passionate baker.

While Austin eventually built a house for Susan and himself called “The Evergreens,” this letter seems to be from before they got married, making me think it’s literal trees, not the home.

The best reference I have here is, literally as always, A Queer History of the United States by Michael Bronski. You can also read the wikipedia on romantic friendships here.

Tantalizing stuff here, amiga! I second Rhody's podcast suggestion. Readings from the poems and letters and letter poems performed, opened up in the context of the time, different voices....

One question. Why say "she always wore white" when the two authenticated photos show her wearing dark duds? Was the white-clad recluse one of Mabel's inventions?

Cheers!

"Like sisters, really" LOL

This was a fascinating read, you could make a podcast on this!