Sometimes, after a hiatus, beginning is the hardest part. Hello, friends. How are you? May was largely difficult, until it became beautiful, thanks in no small part to a visit from U.S. shapeshifting wonder artist Xena Zeitgeist. We spent a week exploring Toulouse, binging Severance, and drinking coffee, and even squeezed in a day trip to Foix. It’s probably my favorite town near Toulouse. The hilly medieval streets enchant a la Beauty and the Beast, a castle on a great hill towers over cafés and shops and patisseries, and the bartenders and baristas are storybook friendly.

On our stroll, we stumbled across a cash-only antique store. Tables fat with bric-a-brac poured out the front door and onto the stone streets - and there sat the most dramatic salad utensils I’ve ever seen: oversized to the point of impracticality (they’re as large as my whole arm), with conch shell handles too thick to grip. One fork tine is missing.

I’d never wanted anything more in my life.

As I handed over ten euro, the seller told me these weren’t just any serving utensils. Oh, no. They were whittled by Jacques Cousteau’s second-in-command and used on their boat. Jacques Cousteau himself touched them, served salad with them, smoked a cigarette in their line of sight.

Look, is it true? Who knows. But the vendor only told me this after I’d paid, so why would he bother lying? And this week, I found a photo of Cousteau’s crew around a table, a piece of wood and a knife strewn among the wine bottles, as if someone were fixing to start whittling.

So for the love of a good yarn, I choose to believe that I, Snail Mail Sweetheart Nikita Andester, wrangle salad using the same tongs as Jacques Cousteau. Stranger things have happened.

And in the name of a good second-hand mystery, today we’ll be exploring another thrifting treasure from the Haute-Garonne, where I’ll unpack…

🐚 a packet of WWI-era letters from the flea market,

🐚 World War One's toll on France,

🐚 local drama in one man's quest for drinking water,

🐚 the tragedy of French bureaucracy,

🐚 and genealogy wins!A flea market mystery

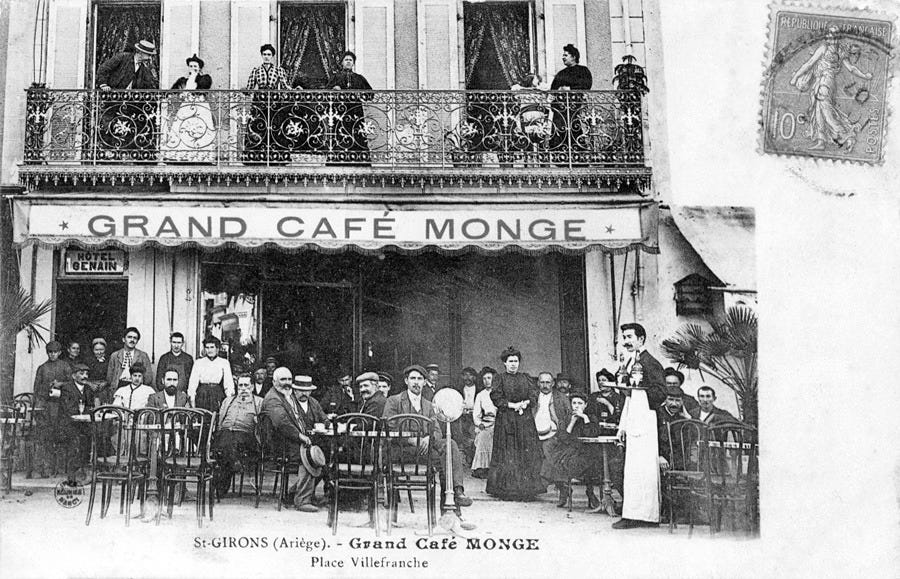

Foix isn’t the only place with second-hand gold. Right here in Toulouse we’ve got the flea market at St Aubin. I’ve written about it before, with its tables and blankets orbiting the church, each vendor’s haul teeming with a chaos of CD players, 400-year-old books, second-hand clothes, vintage nudie mags, and early 20th-century furniture1.

And, of course, old photos and letters. Mid-century postcards, turn-of-the-century portraits, you name it, it’s here - including a packet of 1917 letters held together with a nail. The letters came from Ariége, the mountainous Pyrénées region a stone’s throw from Toulouse. I bought them without a second thought. And pulling out my intermediate French skills2, I got to work.

It started with a simple request

In 1917, when spring unfolded and winter released its grip on the soil, a small hamlet in the Pyrénées decided it was time to move their fountain. The public’s primary source of drinking water was inconveniently located for most residents, and after putting in a construction order, Monsieur Caubet, the man overseeing the change, assumed the well would be in its proper place come summer.

Before tap water, the communal fountain or well was essential to daily life. Wells provided, duh, water, but they also were a cornerstone of a village - all tasks, from cleaning the house to gossiping to making soup, first went through the fountain.

And as the First World War left millions of French soldiers wounded, some folks returned home with less mobility than before. Many others died, leaving the French population older than ever - with all the accompanying aches and pains. It’s easy to understand, then, why moving the fountain was critical for Caubet’s hamlet. And unfortunately for him, the job wasn’t getting done.

Frustrated, Caubet contacted a government lawyer named Léopold Labayle from the nearby town of Saint-Girons. While I don’t have Caubet’s letters, the context is clear. The drinking source for the hamlet should’ve already been moved, but one man was giving the town grief, hellbent on keeping the fountain right where it was.

Enter our villain: One Monsieur Cau Bourdisse.

Our first letter begins 9 May 1917 with Léopold’s response to Caubet’s plea:

Almost immediately, Léopold is fired up about get Cau Bourdisse. Cher Monsieur Caubet, he begins…

This case is being argued at Oust’s Justice of the Peace.

…The process will be fast… if Cau Bourdisse wants to take the matter to Saint-Girons [to contest it], he’ll be forced to take the lead.

Your situation looks good… I’m notifying the mayor via the bailiff, so you can cite that Cau Bourdisse is putting the fountain back in its original place, and make it clear that this fountain is communal.

If you’ll be so kind, post me the… provisional 100 francs.

Receive, Cher M Caubet, my best salutations.

L. Labayle

But as every French resident knows, May isn’t the month for getting work done. Nor June. Nor July. Nor August. Summer beckoning, Léopold went about his merry way, letting neither war nor community fountain deny him some down time. Perhaps he went to the Narbonne beach, unwound in the mountains, or slurped down Catalonian tapas.

Whatever the case, Léopold didn’t write again til 21 September, when he returned from holiday and, to his horror, discovered that Cau hadn’t moved the fountain. You can practically taste Léopold’s apology and frustration here:

Cher Monsieur Caubet,

I’ve just returned from holidays, and I’m at your complete disposal regarding the matter of Cau Bourdisse. I’ll assign Cau to the Judge, then to your village straight away, like you want. I await your orders.

When you come to see me, I pray you’ll bring me the 100 francs provision to get the process going.

Four months of silence is a long-ass time, but in Léopold’s defense, Caubet hadn’t sent the money, either.

It’s easy to understand why (not only because Caubet was also enjoying les vacances3). At the time, a hundred francs was about 260€ ($2954) - and with the war at hand, money wasn’t something to spend lightly.

The Great War’s far-reaching fingers

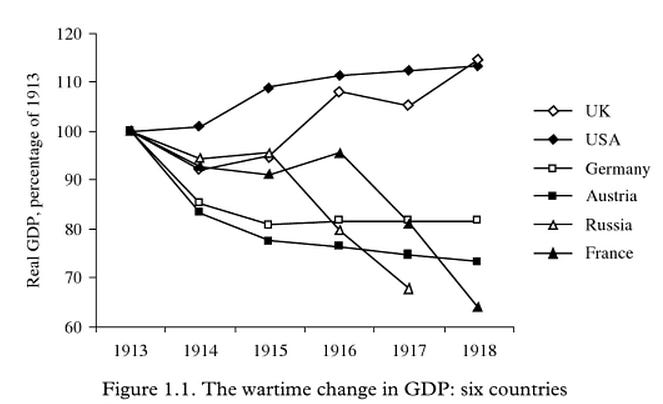

World War One battered France’s pocket. The front line in the east was home to most of the country’s food production, and trench warfare decimated nearly two million hectares (7300 square miles) of farmland, impacting the financial security of even cached away regions like Ariège.

But France was facing an even greater existential problem. By 1917, the war had already killed roughly one million of the country’s twenty million men. If you’re reading on the bus, at a café, in line at the grocery store, take a second and notice the men around you. Picture one in twenty gone. Dead. In your neighborhood, your school, your favorite bar. This loss stunted the nation’s birth rate; by the start of the Second World War, France’s population was the oldest in the world5.

By the war’s end, France had lost 1/3 of their pre-war output6, producing far fewer goods and struggling to keep themselves afloat. And that was a strike that even the west, safeguarded by the Pyrénées, could feel.

Words of reassurance

With the country reeling around them, it’s easy to understand why the hundred francs gave Caubet pause. And it seems Caubet expressed his trepidation to Léopold, a move that brought the two men closer. By 24 October, his reply bordered on chummy:

Cher Monsieur Caubet,

I’ve received your letter. Don’t be emotional or troubled by such little things. The collector wants the prefecture’s administrative paper with a hundred francs; give him all of it. It can’t hurt… You have right and justice on your side, and rest assured that if you didn’t have everything [in order], I wouldn’t engage in this process. The law is all behind you… everything is in your favor. It’s for this that I said to you and say to you: “You’re on the right path; keep going…”

When one does their job, one can lift their head - and I’m not used to lowering it. The truth has but one face. Laugh at the rest.

Léopold’s advice is so kind, it’s nearly paternal. Odds are, both men knew someone who’d died, and both knew that, safe as they were in the Pyrénées, mustard gas crept across trenches in a breathless nightmare in the east. Compassion and mutual support must’ve seemed like the least they could do.

The sharp blade of bureaucracy!

Cau apparently missed that whole compassion memo. In November, the well still not moved, Léopold jotted a note to Caubet to say he was summoning an audience with a clerk from Oust, Cau Bourdisse, and the mayor of Érce.

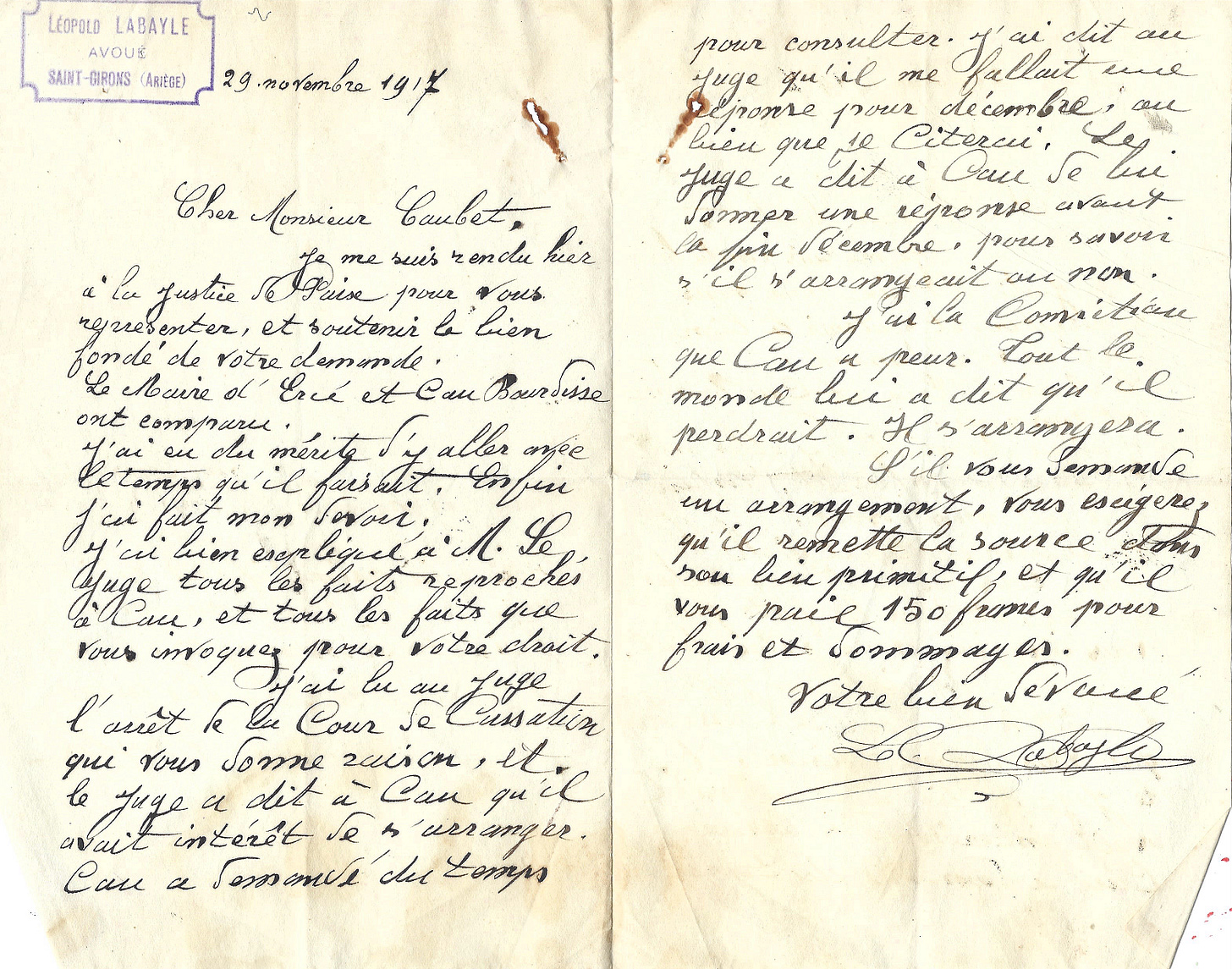

The threat of so many authorities seemed to do the trick, and after the meeting, Léopold wrote Caubet on 29 November, ebullient:

At the meeting, Léopold says,

I thoroughly explained all the facts needed to advocate for you to the judge, and all the facts blamed on Cau.

… the judge told Cau that he had to solve the issue. Cau requested some time to consult. I told the judge I needed a response by December, after which I quote: the judge told Cau to give a response before the end of December about whether he could arrange it or not.

I have a feeling Cau is afraid. Everyone told him that he lost. He’ll arrange it.

If he asks you for a deal, suggest he put the well back in its initial location, and that he pays you 150 francs for fees and damages.

Your always devoted,

L. Labayle

While I love seeing two bureaucrats bond over a common nemesis, I can’t help but wonder: Why was Cau refusing to move the fountain? I’ve been playing with possible explanations: he once tripped in front of the village boulanger who laughed at him, and ever since then Cau hated the entire village; Cau was wickedly depressed and struggling to get out of bed, let alone do repairs; Caubet had come over for dinner once and had terrible table manners, and Cau’d be damned if someone so rude bossed him around.

I don’t know. What’s your best guess?

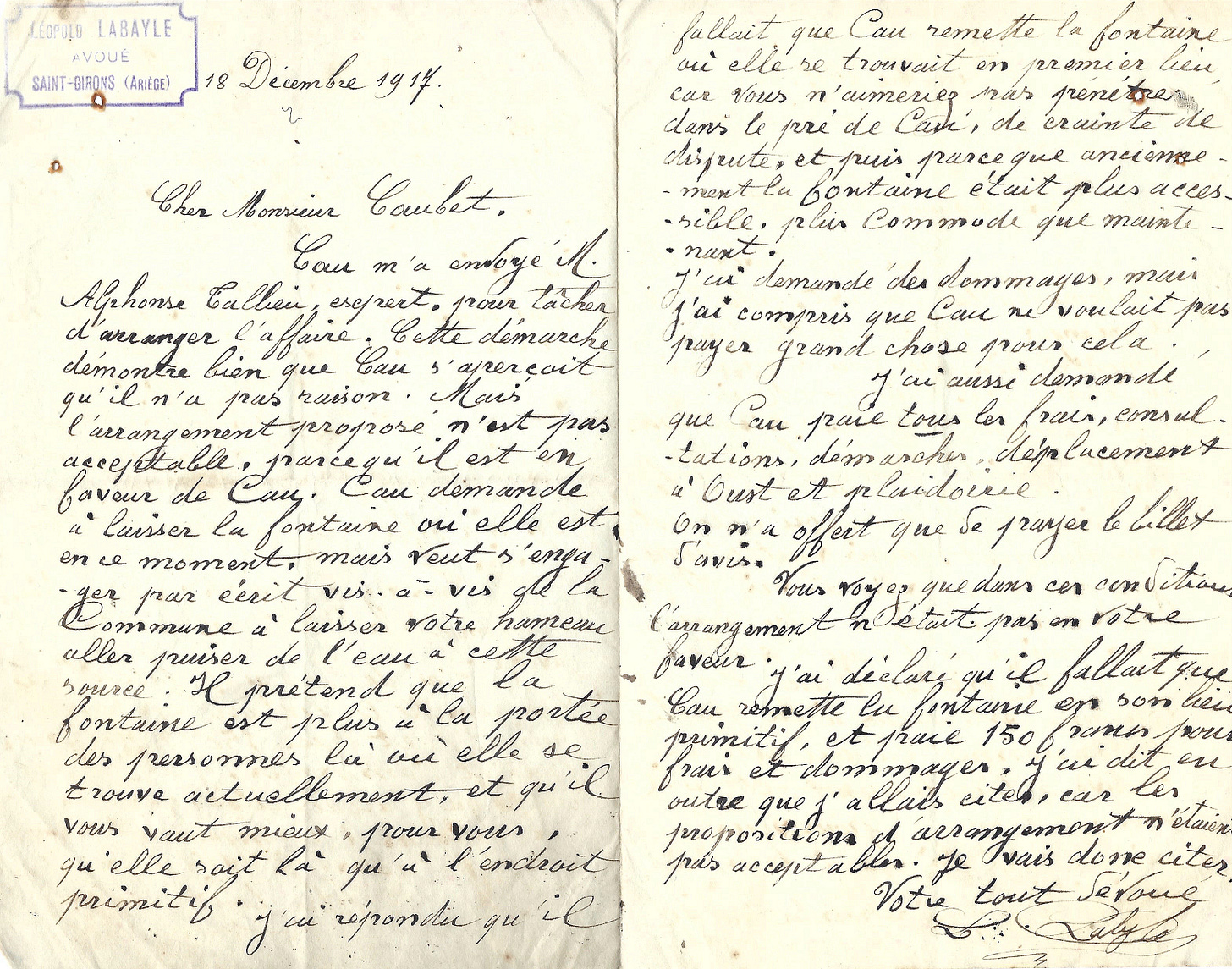

What we do know is that Cau dragged his feet for so long, our boy Léopold went ahead and shoved him before the judge. And by mid-December, Léopold’s affability flew out the window:

Cher Monsieur Caubet,

Cau sent me Monsieur Alphons Callieu, an expert, to try and arrange the matter. This shows me Cau knows he’s not in the right. But the arrangement Alphons proposed is unacceptable since it’s in Cau’s favor. Cau asked to leave the fountain where it is at the moment, but wants to commit in writing… that our department says your hamlet should draw water at this source: he’s pretending that the fountain is more accessible for people where it’s currently at, and that it’ll be best for you if it stays in this spot.

I responded that Cau had to move the fountain… I asked for damages, but understood that Cau didn’t want to pay much…

You see that under these conditions the arrangement wasn’t in your favor.

I said that Cau had to put the fountain in its initial spot and pay the 150 francs for fees and damages. I said that I’d also cite him; the proposed arrangements were unacceptable. I’m going to give him a citations.

Apparently that went over as poorly as you can imagine; like a caricature of a bully, Cau called in backup - and failed once again.

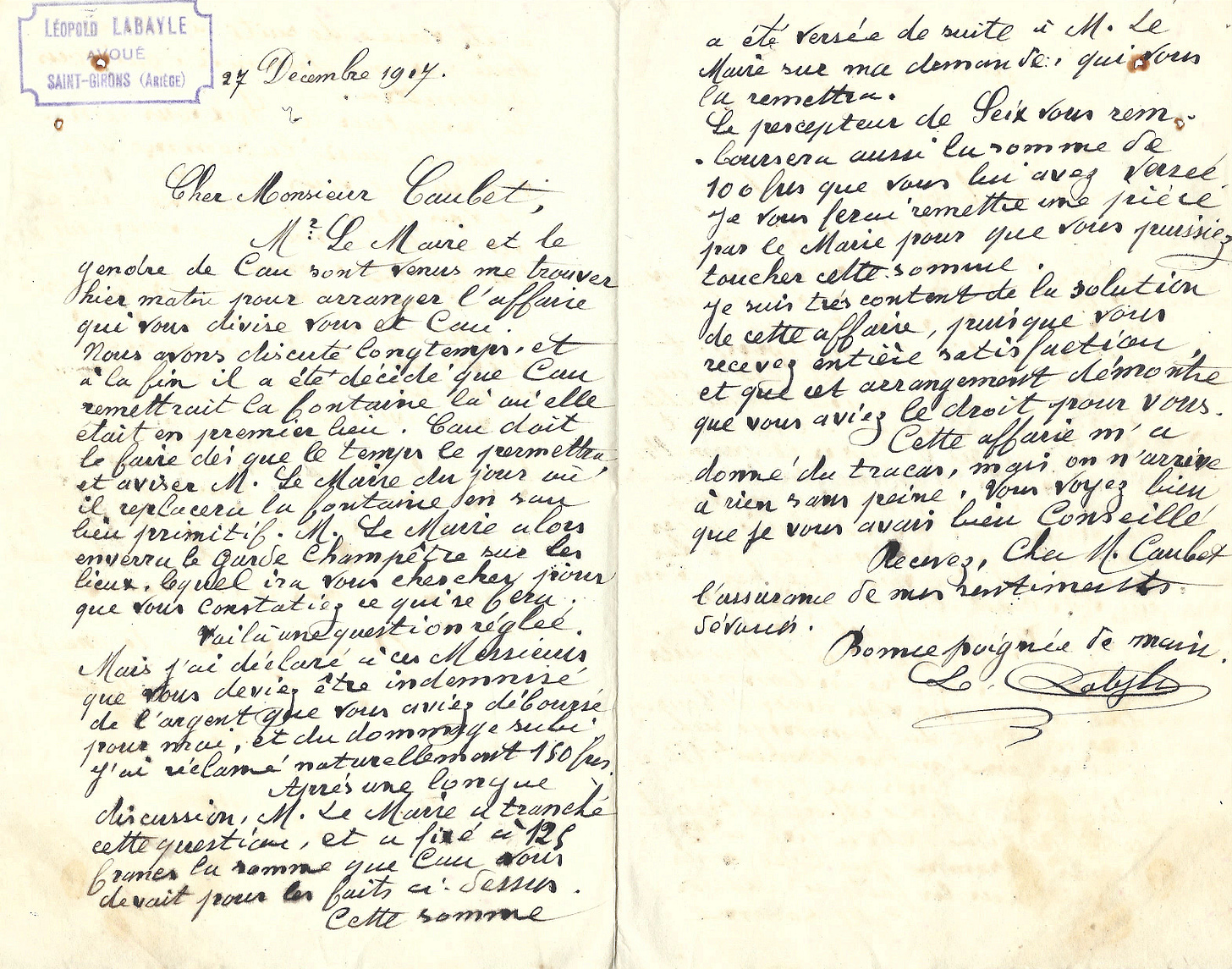

Cher Monsieur Caubet,

Monsieur le Mayor7 and Cau’s son-in-law came to visit me yesterday morning to arrange the affair dividing you and Cau.

We talked for a long time and in the end decided that Cau will put the fountain back in its original location. Cau must do it in the time permitted and keep the mayor up to date… The mayor then will send the countryside warden to the sites to verify it happened.

So that’s one question settled. But I said you should be given the money you dispersed in May and, for the subjected damages, you should naturally be returned those 150 francs.

After a long discussion, the mayor… decided that Cau must give you 125 francs for all the disappointment.

This sum was immediately paid to the mayor at my request, which he’ll send to you… This affair’s caused you trouble, but one arrives at nothing without pain. You’ll see.

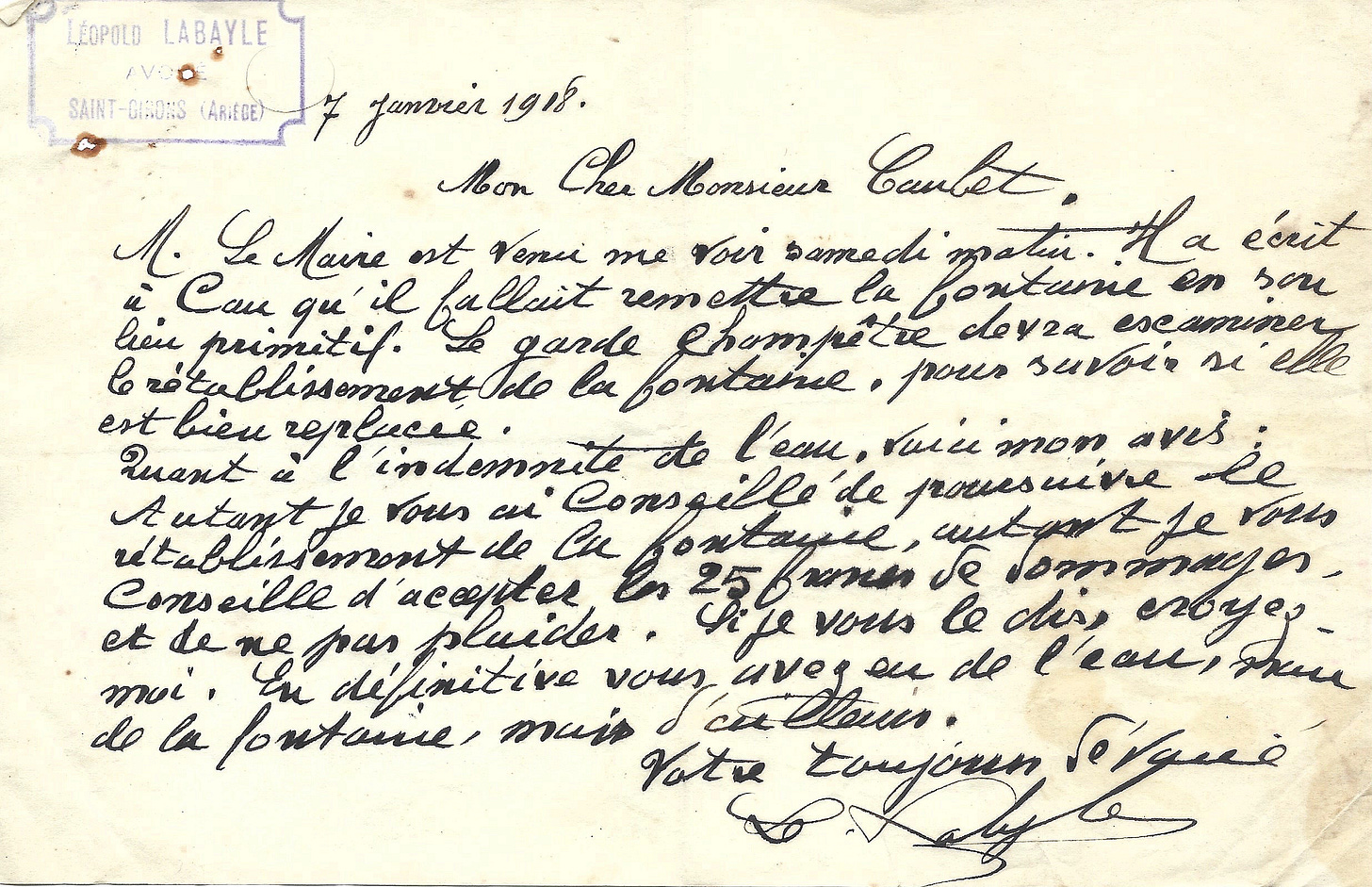

Passing the buck, changing departments to contact, rallying behind a common enemy - these bureaucratic dances are as quintessential to French culture as wine and protests8. And despite all Léopold’s confidence, with the new year, he wrote once again - to find nothing changed.

But the mayor returned to smooth things out. And with the countryside warden’s promise to oversee the fountain’s progress, Léopold softened his tone.

…even though I recommended you pursue the reestablishment of the fountain, I advise you to accept the 25 francs in damages [on top of the 100 reimbursed] and not litigate.

But when nine days passed and Léopold received no updates, his old frustration crept back in:

Cher Monsieur Caubet,

Has Cau put the fountain back in its original place? The weather’s beautiful, and he has no reason now to not put it back where it was before.

If he doesn’t get it done, we’ll have to fine him this month.

Your always devoted,

L. Labayle

And with absolutely no faith in Cau left (if ever there was some), Léopold doubled down two days later.

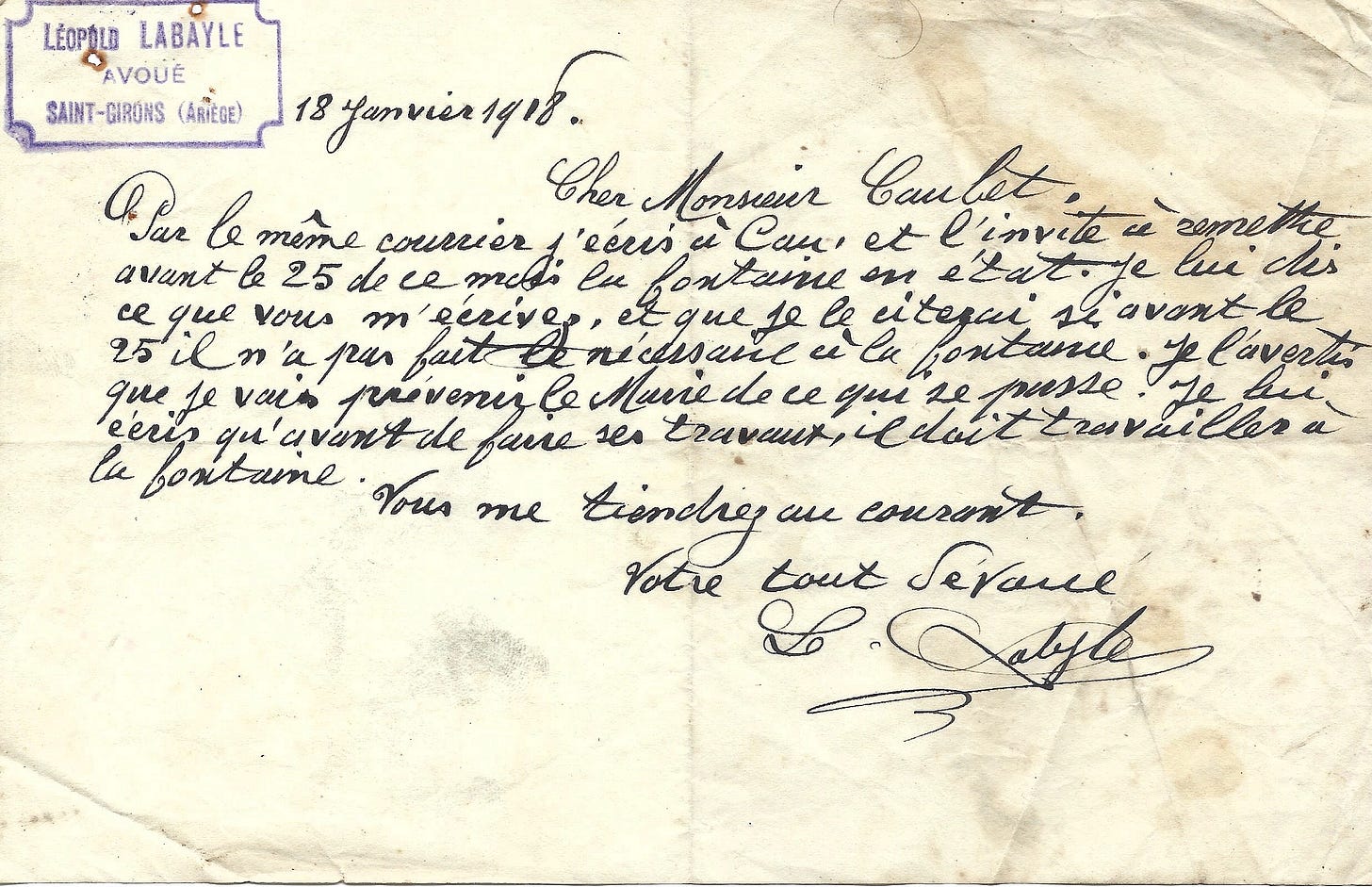

Cher Monsieur Caubet,

By the same courier, I wrote to Cau and told him to put the fountain back by the 25th… I’ll fine him by the 25th if he hasn’t done what the fountain needs. I warned him that I’m going to inform the mayor about what’s happening…

Before doing his [other] repairs, he has to work on the fountain.

You’ll keep me up to date.

Always your devoted,

L. Labayle

And with this short letter, their correspondence ends. I’d like to believe Cau finally took the hint and, more than eight months after Caubet’s first letter, moved the fountain. Whatever the case, Léopold was at his limit, and I can imagine that if Cau dallied a day longer, a fine arriving at his front door might’ve finally spurred him into action.

But knowing French bureaucracy, can we ever really be sure?

History lives!

In two years of Snail Mail Sweethearts, this is my first time researching something from my own neck of the woods. Despite many towns coming up in the letters, the region itself isn’t very large:

While digging around online, I found a living descendent of Léopold Labayle on Geneanet, the French equivalent of Ancestry. While this flea market find makes for a good conversation piece, I can’t imagine a greater gift than connecting with a descendant and giving them the letters. If someone out there had a packet of letters written by my great-great grandparents, I’d be desperate to trace my fingers over their handwriting.

This week, I’ll be signing up on Geneanet and contacting Labayle’s descendant who put so much love into building their family tree. If I’m lucky, maybe they’ll want to meet up and tell me more about Léopold. Regardless, you can bet I’ll share the outcome here.

All my love and long lost letters forever,

Nikita, your Snail Mail Sweetheart

Yes, these are all actual things I’ve bought there.

I’ll have you know I read all three Hunger Games in French this month!

OK, legally, les vacances didn’t exist for all employees til 1936, but the energy has been there since the Middle Ages.

Good fuck the USD right now - anyone wanna hire me for European art or writing projects? Haha, just kidding… unless…

Worth nothing that this is just out of countries who were tracking this data.

The Economics of World War One, edited by Stephen Broadberry and Mark Harrison

Of Érce, most likely.

Currently in the thick of changing my visa status and (finally) getting my carte vitale, I can confirm that not much has changed in the past hundred years.