A changing season is something to behold. For me, it’s always a balance beam routine where I juggle anxiety and nesting, prepping for the next phase. Do you feel that urgency and tenderness, too?

Maybe it’s that my day job has been pretty dang busy, or that Rhody and I had the absolute gift of hosting two friends (and Postcard Club angels!) back to back1. One of them came all the way from Colorado and we went to see cave art in Ariege at Grotte de Niaux. Fellow history nerds, I don’t think I’ve ever seen a cooler thing in my life than 14,000-year-old artwork.

The day our friend caught a plane home, I filled the America-shaped hole he left behind with food. Rhody and I hosted friends for dinner and served the most quintessential American autumn dinner we could wrangle: chili, cornbread, and hot apple cider.

Friends, it slapped. I don’t generally trust French people to handle spicy food, but they were champs. And between the chili, the cornbread, and a new novel-in-progress about witches and agoraphobes in the Old West, my September’s well on theme with today’s topic.

This week, instead of a specific set of letters from one person, we’re exploring the whole damn history of the chaotic Pony Express.

Giddy up!

🐎 The Pony Express gets its legs

Before I started researching the Pony Express this month, I hadn’t realized just how brief its tenure was: for only 18 months, cowboys giddied-on-up between Missouri and California, as fast as they dang could, to deliver mail across the country.

Before the Pony Express, sending mail west was a shit show. East Coast news routinely took a month to reach California, and news from across the Atlantic would take about ninety days2. In 1850, mail was so slow that Los Angeles didn’t learn California had joined the Union until six weeks after it was voted in3.

This 1901 essay said loneliness - in part due to the lack of letters from home - killed countless young people who’d ventured out west back then. “I know we laugh at a homesick individual4,” the author says, “but a genuine attack of the disease is no laughing matter. The medical reports of the Union Army during the Civil War attribute no less than 10,000 deaths to nostalgia, the medical name for home-sickness.”

(Who’s to say how much homesickness contributed to the scheme for the Pony Express, but with such a staggering statistic, I had to share.)

With no mail coming in, folks got desperate. The government spent a decade postulating that camels might be the best way to deliver mail, hypothetically crossing from New York to California, through the deserts, in just fifteen days. In 1855, then-Secretary of War and future Confederate dirtbag Jefferson Davis took that idea and ran, convincing Congress to allot $30,000 to import camels (today that’s a bonkers $1.1 million, or €975k for my E.U. buds5).

In 1857, the U.S. brought 75 camels overseas. But unfortunately for us, the vibe had changed. The camels were no longer meant for delivering love letters to lonesome cowboys and vaqueros, but for the Army to continue its sprawl across the continent.

Even with camels stomping across the deserts, California’s connection to the East was still shoddy at best, delivered through a slogging coach route that cut through the South. As tensions brewed between what would become the Union and the Confederacy, the Northern states were eager to secure a line of communication that avoided these increasingly hostile regions.

California Senator William Gwin got vocal about the mail crisis, and with dollar signs for eyeballs, an entrepreneurial soul stepped up, offering a solution in the form of the Pony Express.

Stage coach company owner William Russell was the first to get involved. Russell is perhaps best known today for defrauding the government. While trying to get the Pony Express up and running, he convinced a federal clerk to help him steal funding from the Indian Trust Fund. They embezzled it without a hitch - until the clerk had a guilty conscience and came clean. Russell and his bud went on trial, but got off the hook thanks to a little thing called the Civil War putting the case on the backburner6.

The money still safely Russell’s - for now - two business partners hopped on board and they got to work, establishing 186 stations between Missouri and San Francisco where riders and horses could relay their way across the whole damn west.

And in April 1860, the Pony Express took off.

🤠 A day in the life

Right from the beginning, folks marveled at how rapidly news now traveled. Peep this excerpt from the otherwise bonkers Salt Lake City Mormon newspaper From Utah, dated April 10th, 1860:

The Pony Express from the West came in last Saturday midnight, being four days out from San Francisco; and from the East it came in at 5 P.M. on Monday last, being six days out from St. Joseph. It… went on through like a flash. It is regarded by persons here who know what it is to cross these plains, as almost the greatest private enterprise of the age… This will be in round numbers 400 miles per day, and is far beyond a parallel in history.

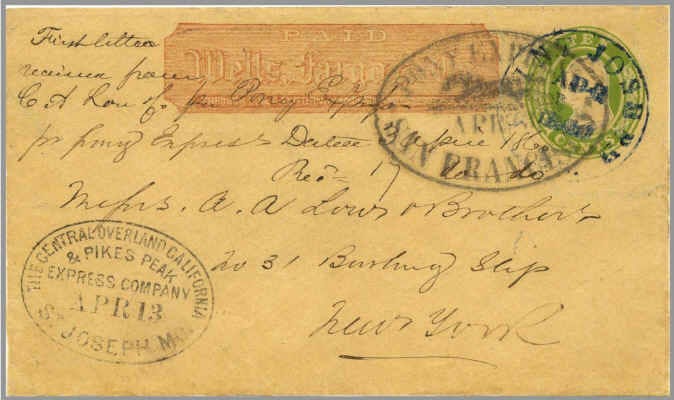

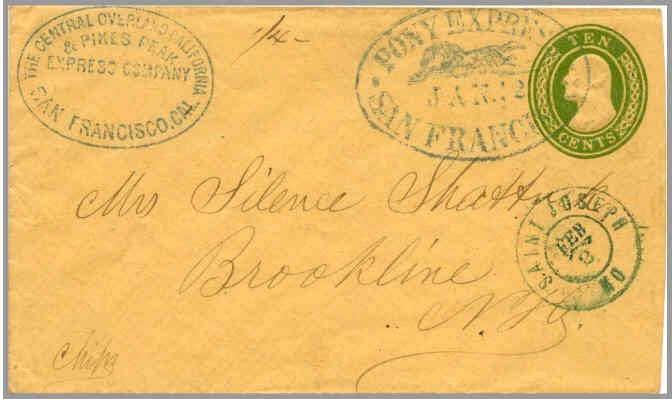

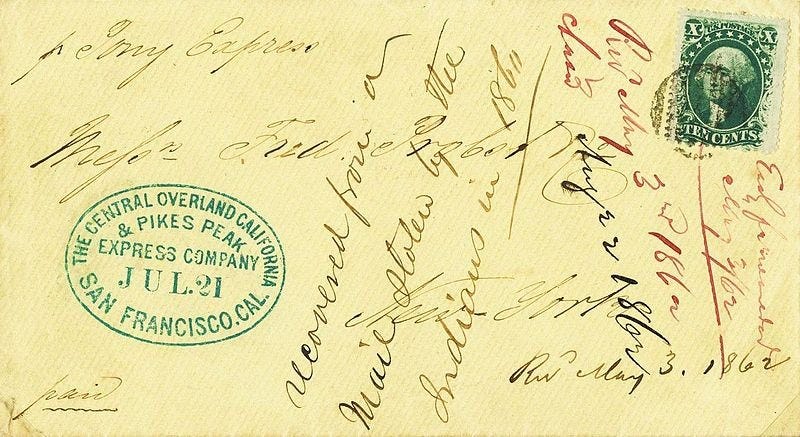

Just a few days later, this exact letter was one of the first to make its way east from San Francisco:

The Pony Express chose riders carefully. In a biz that relied on folks pushing horses to their limits while carrying buttloads of mail cross country, size was money. Sort of like today’s expectations for jockeys, the average Pony Express rider weighed no more than 125 pounds.

Because of the size limit, the average age of these riders was around twenty, but kids as young as fourteen took the job, earning a hearty $25 a week - about $950/€860 these days. One helluva salary back then (and now).

All that pay wasn’t going to lavish expenses, either. The Pony Express stations were often little more than a makeshift house with another guy hanging out, holding onto two horses. One to swap, and one to rest for the next rider7.

In an effort to preemptively tamp down on any benders or the dizzying effects of making good money (which I’ve covered before), every rider had to pledge an oath upon getting hired:

“I do hereby swear, before the Great and Living God, that during my engagement, and while an employee of Russell, Majors and Waddell, I will, under no circumstances, use profane language, that I will drink no intoxicating liquors, that I will not quarrel or fight with any other employee of the firm, and that in every respect I will conduct myself honestly, be faithful to my duties, and so direct all my acts as to win the confidence of my employers, so help me God.”

Gotta love/hate how the men in charge put themselves on the same pedestal as God. But as with any overbearing expectations bosses foist upon us plebes8, the Pony Express rider broke just about every rule as often as possible.

Richard Burton, a British traveler who found his way to the Pony Express stations, swore the riders were anything but saintly. In his travel memoir designed to titillate tight-laced British audiences, he said booze a’flowed at Pony Express stations, and he “scarcely ever saw a sober rider.” But that wasn’t all. When it came to propriety, Richard said,

“as for profanity… they would make the blush of shame crimson the cheek of the old Isis bargee9; and, rare exceptions to the rule of the United States, they are not to be deterred from evil talking even by the dread presence of a " lady”… I met one gentleman who owned to three murders10.

It’s no surprise they got their kicks where they could. This job was harsh. Riders galloped at full speed the ten miles between each station, jumped off the horse, and hopped onto a fresh one, over and over, covering an average 125 miles a day11.

You ask me, the guys deserved a lil drink. Maybe not the murdering, though.

📩 A swift end

From the get-go, the Pony Express was bleeding cash. Maintaining 186 stations and paying high wages to the riders and the station employees cost a pretty penny. And early on, the proprietors ran into shit luck when a blizzard killed off a bunch of oxen hauling Pony Express supplies, costing Russell and his partners even more.

But that wasn’t the only thing plaguing them. Their business model just didn’t make sense for average folks trying to send a letter. Before researching, I’d imagined tragic love letters rushing their way across the states, connecting a lonely and desperate Miner ‘49er to his lover back home. But in reality, the Pony Express was too damn expensive. Shipping cost $5 an ounce - $189 by 2024 standards. For my non-US buds, that’s €171 to send a piddly 28 grams of mail12.

Now, I may be wildly sun-kissed in the blazing endless desert of my love for Rhody (see the first photo for reference), but even I don’t think I’d swing for a $200 love letter all too often.

Even when the Pony Express slashed the rate to a buck an ounce, the damage had been done. Rather than average citizens using the service, the Pony Express’ main customers were newspapers and businesses. No lonely cowboy smelling a letter for a whiff of a lover’s perfume or cologne here.

The business was in trouble. In just eighteen months, they’d spent $480,000, bringing them to a net loss of $200,000 - over $7.5 (€6.8) million today13.

But a good chunk of that loss came from one final event we didn’t learn in history class: the Paiute War.

The Paiute War

Also known as the Pyramid Lake War, the Paiute War was a month-long conflict between the colonizers and the local Paiute people following simmering disquiet that had been mounting for quite some time. Tension bubbled over in 1860 when the Paiute people - along with other tribes - ransacked and burned a Pony Express station.

While some brief recountings - like this one from Brittanica - make it seem as if these attacks were unprompted, the reality is far different.

The war itself may have only lasted a month, but the disputes began long before, starting with disrespect on Paiute land. The encroaching colonists disrupted Paiute water sources, and their herders led cattle through vegetation that the tribe relied on for food, trampling it. For three years, the Paiute tried to adapt peacefully. But in May 1860, two white men at Williams Station - a Pony Express waypoint that also served as a saloon and general store - kidnapped and assaulted two twelve-year-old Paiute sisters14.

In a rescue that allegedly included the girls’ father, a chief and seven warriors stormed Williams Station, finding the girls tied up in a cellar. The warriors killed the kidnappers, along with three other settlers, then burned Williams Station to the ground15.

War had begun.

The first major Battle of Pyramid Lake was a decisive victory. The militias, thinking the Paiute people wouldn’t be well-prepped for battle, rolled up assuming they’d sweep in and out, victorious. But the Paiute fighters were fed up - and prepared. The battle was swift, and out of about a hundred militiamen, 76 died. No Paiute casualties were reported.

For the second major battle, the militias came armed and in great number. Bolstered by men from Sacramento, they returned to battle with an army of over 800. But similarly as prepared, the Paiute didn’t cede. And after a grueling three hours of fighting, only three militamen had died, and the Paiute people suffered little to no losses16.

Declaring the war an official draw, the Paiute, their allies, and the colonists decided to keep things neutral - for now. The Paiute people still live around Pyramid Lake to this day, commemorating the war with a sunrise ceremony and, interestingly, an annual run.

Brief as it was, this war cost the Pony Express $75,000 (today that’s $2.8/€2.5 mil) in lost goods.

A final death knell, spelled in morse

Even with the war, the Pony Express was still yippee-ki-yaying its way across the continent, delivering mail from one coast to the other.

But one nail in the coffin cemented the end of this here Yeehaw Express: On October 24, 1861, telegraph wires crackled to life from New York City to San Francisco. The cities were connected, and sending messages now took hours, not days17.

Two days after the first telegraph crossed the continent, the Pony Express shuttered for good.

I’ve read different reports on how the proprietors felt about this. Some sources say that Russell and his co-founders knew dang well the Pony Express would only last til the telegraph got up and running, which could explain the reckless business model. Others paint the abrupt downfall as a surprise. But either way, with the connection of some wires, telegraph operators - often young women, a rad story for another day - took the helm, relaying hot goss and national news across the continent. The country was connected overnight.

The Pony Express was kaput, except for in Americana imagination, where those slender, foul-mouthed riders are still alive and kicking.

Bonus reading:

This was so much fun to research - here are two original sources that you should check out:

Go to the bottom of page 169 here for part of an 1860 Kansas Star article describing the very first ride on the Pony Express.

Check out this diary kept by a U.S. soldier during the Paiute war. Brutal, sad, fascinating.

See ya soon, my roamin’ pardners!

Did y’all learn about the Pony Express in school? Tell me a factoid about it that I didn’t cover!

My bonus fact is that Buffalo Bill apparently was probably lying about his former life as a Pony Express rider, despite his whole career basically hinging on claiming to be one.

In the meantime, all my love and pony-petting enthusiasm,

Nikita, Your Snail Mail Sweetheart

Sign up and perhaps you, too, can have a free air mattress to rest your pretty head on in France! (or send me an email and I’ll pencil you in for free, bub)

“The Story of the Pony Express” by Nancy Pope, for EnRoute Magazine (The National Postal Museum’s former newsletter), 1992

Do we? Were people just assholes back then? Was this a cultural norm?

War Drums and Wagon Wheels: The Story of Russell, Majors, and Waddell by Mary Lund Settle and Raymond W Settle. Settle, 1966.

Looking at you, kombucha company CEO who said I didn’t “prioritize the company” when I dared schedule a major surgery during (I shit you not) his vacation.

For anyone else baffled by what this means: Isis is another name for the River Thames in southwest England. Barges along the shore held rowing facilities and spots to watch folks row. I guess those people had some real potty mouths. If you have firsthand knowledge on this, fill me in! Gimme the hot rowing gossip!

From The City of the Saints: and across the Rocky Mountains to California by Richard Burton, published 1862

”150 Years Later, Pony Express Rides on in Legend” for NPR’s Weekend Edition, April 2010

"Taking Stock of the Pony Express" by Frederick J. Chiaventone for Wild West Magazine, April 2010

I can’t find a definitive number on casualties, if any, other than all resources saying it’s “low to none” - comment if you have a resource!

“The Transcontinental Telegraph,” NPS Website

🥰🥰🥰